Buy Commercial or Lose

The U.S. risks its national security by not harnessing commercial tech for defense.

The Pentagon will spend nearly $150B annually on research and development of weapon systems to be delivered in the 2030s. To deter China in this decade, it must also invest in procuring commercial products and services that can be delivered in the next few years.

This is why Mike Brown and RADM (Ret) Lorin Selby have called for a Hedge Strategy to rapidly acquire many small weapon systems leveraging emerging technologies and Dr. Kathleen Hicks, Deputy Defense Secretary, champions the urgency to innovate by harnessing commercial technologies. The DoD’s CTO highlights 14 critical technology areas for defense - 11 of them are commercially driven.

The threat of conflict with China is increasing and the PLA fields new weapon systems at a record pace. The DoD is retiring aircraft, ships, and subs faster than new systems are delivered, leading to an overall decline in forces. Most of the DoD’s major weapon systems critical to deter China won’t be delivered until the 2030s.

While the CCP has civil-mil fusion, the U.S. federal bureaucracy deters U.S. tech companies from defense markets. Yet many leading tech companies are still eager to offer defense solutions. DoD and Congress must complement the major weapon system development by acquiring vastly more commercial products and services.

The law requires the government to show a preference for commercial products and services, yet many across the DoD and Congress insist on developing new systems. Decades of bureaucratic practices and conflicting incentives drive pursuit of non-commercial sources.

Title 10, Section 3453 (formerly 10 USC 2377) requires agencies, to the maximum extent practicable, to define requirements in terms of functions to be performed, performance required, or essential physical characteristics. This is to ensure commercial products or services may be used to fulfill the requirements and commercial offerors may compete in the procurement. The law requires acquisition executives to the maximum extent practicable:

Acquire commercial services, products, or non-developmental items .

Require prime contractors and subcontractors to do the same.

Conduct market research prior to developing specifications or soliciting bids to determine whether there are suitable commercial products, services, or NDIs.

Congress included over a dozen related sections in the FY16-23 National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs). It reinforces with the DoD preferences for commercial solutions along with streamlined practices and pilot programs to acquire emerging tech. The Senate’s FY24 NDAA Sec. 806 requires USD(A&S) to conduct a feasibility study on reducing barriers to acquisition of commercial products and services.

Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) Part 12 and Part 13.5 outline acquisition of commercial products and services along with DoD’s Defense FAR Part 212.102 and Part 239.101 which includes:

Contracting officers, IAW 10 USC 3456, shall treat services provided by a business unit that is a nontraditional defense contractor as commercial items.

DoD recently implemented the final rule within the Defense FAR, based on the FY22 NDAA, to acquire innovative commercial products or services through Commercial Solution Openings. DIU led the adoption of these novel practices which include fixed priced contracts and more streamlined procedures than traditional FAR contracts.

Expanding the National Security Innovation Base

Anduril founders recently discussed on a podcast how companies like Palantir and SpaceX had to use this law to sue their way into the defense sector and now offer disruptive solutions. These stories have been told many times over the last few years, but there continues to be a struggle in changing how DoD does business.

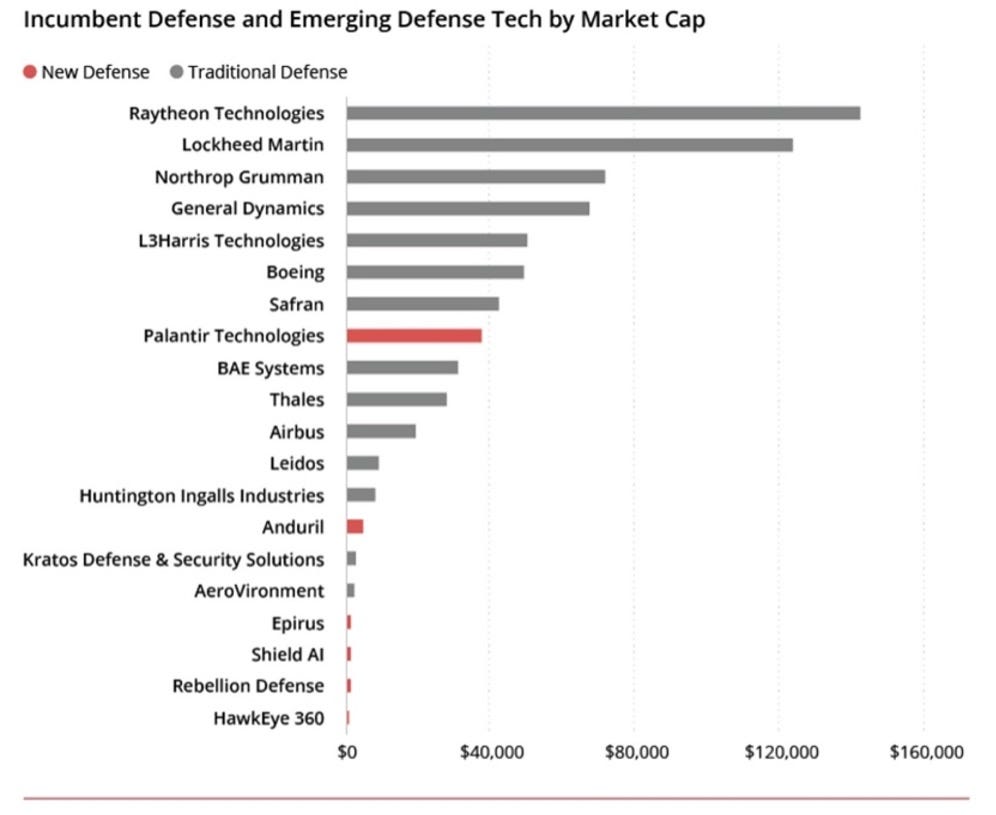

There are six Defense Tech Unicorns - venture capital backed startups who have a valuation over $1B - Palantir (now public), Anduril, Epirus, Shield AI, Rebellion Defense, and Hawk Eye 360. Beyond them are dozens more emerging defense tech and dual use tech startups making great progress in defense to include: Applied Intuition, Hermeus, ScaleAI, Peraton, Capella Space, Vannever Labs, and Saildrone. Applied Intuition along with other tech companies and venture firms penned an open letter to the Secretary of Defense imploring him to harness commercial innovation.

Source: Avacent Apr 2022

These companies are eager to exploit leading technologies and apply modern digital design practices to the defense sector. They seek to understand the DoD’s demand signals from operational challenges, leadership strategies, and projected budgets. They invest their own R&D to design, develop, and test solutions - hardware and software - to then sell to the DoD.

This runs counter to the traditional model of spending a decade or more to write requirements, conduct extensive analysis, develop countless strategies, design, develop, and test a system though a labyrinth of reviews and processes. What’s worse, while sacrificing “speed of delivery” to get it done right, DoD still doesn’t have the greatest track record. The traditional model can’t keep pace with the changing operations, threats, and technologies.

The defense industrial base continues to shrink five percent annually and lost 40% of small businesses over the last decade. DoD requires bold moves to regrow the base to harness America’s leading companies and talent for national defense.

If the DoD can modernize its requirements, acquisition, and budget processes, along with strategic direction and culture to embrace commercial models to complement traditional ones, it can unleash massive speed, agility, and innovative solutions for our warfighters.

Barriers

Requirements

The DoD’s Joint Capability Integration Development System (JCIDS) process is an outmoded, bureaucratic nightmare that can take years to define and approve program requirements. One of the most infamous examples is DoD wasted 10 years in requirements and analysis for a new handgun. JCIDS is overly focused on defining requirements for individual programs instead of framing operational needs, challenges, and opportunities. There is often a bias for the new system to be modern versions of the 30-year-old legacy system. The policy and manual to navigate JCIDS is over 500 pages and growing! To validate interoperability, JCIDS mandates program documents include a dozen architecture views that comply with an archaic framework that hasn’t been updated since 2010. While the law exempts rapid and software acquisition programs from JCIDS, the bureaucracy still seeks to insert themselves.

In this digital age with complex models for designs, digital engineering, and integrated solutions, we can no longer afford to operate in an analog model pushing papers around the Pentagon. Requirements can no longer be defined without a robust understanding of commercial solutions and tech maturity to shape the trade space.

Antiquated Acquisition and Contracting Strategies

Once the acquisition community receives the requirements document, which already constrains the solution space, it develops acquisition and contracting strategies. It can take years to go through the upfront planning and analysis phases, which can include competitive prototyping, before finalizing system requirements and contract solicitations. How program offices conduct market research varies widely by organization. Some engage industry early and often to understand their capabilities, the leading vendors, and solicit feedback to shape their strategies and solicitations. Others issue requests for information and conduct simple searches to identify interest with limited opportunities for insights and discussions prior to issuing a request for proposals. While Congress chides DoD to go faster, some appropriators continue to scrutinize and sabotage rapid pathways.

Novel acquisition and contracting practices emerged over the last few years to operate with greater speed, agility, and success—without compromising oversight or outcomes. However many are reluctant to adopt these practices or leadership drives them to traditional acquisition pathways and lengthy FAR Part 15 based contracts. These typically include spending years in upfront documentation, analysis, and reviews. There will often be 12-24 months between requesting proposals and awarding the development contract. Given the extensive time and energy to develop and compete these strategies and contracts that cover a decade of development and production, these are often winner-take-all contracts instead of multiple awards that foster continuous competition.

As traditional defense primes invested resources and have decades of experience navigating the bureaucracy, they continue to capture the lion’s share of defense sector contracts. The selected vendor then dominates a sector for the next decade. Those not selected may leave the sector, driving a loss of talent and resources. The selected vendor can then operate with greater monopolistic power with less pressure to control costs, schedule, and performance. They secure intellectual property rights requiring the government to fund them throughout the system lifecycle for maintenance, upgrades, and re-engineering obsolete parts decades later.

Long, Constrained Budget Cycles

If a DoD executive or operational commander identifies a mature commercial solution that would benefit their mission, it would likely take a few years to fund within the defense budget. Many startups, small businesses, and nontraditional defense companies will develop successful prototypes for the DoD, then be asked to wait years for DoD to request and Congress to appropriate funding to develop and scale the solution. DoD’s plans via five-year budget timelines and during any given point in time is planning, budgeting, or executing three separate fiscal year budgets. This delays deployment of capabilities and often results in capabilities being outdated before they reach the hands of the warfighter.

Congressional appropriators segmented the defense budget into >1,700 separate accounts for acquisition programs to ensure proper oversight and control. Hundreds of these accounts are under $20M. Shifting more than $4-10M between accounts requires a lengthy approval process across the Pentagon and all four Congressional defense committees. If DoD was presented with a novel commercial solution that they valued higher than other capabilities in the budget, it can easily take six months to request a funding transfer, with no guarantee of approval.

Pricing Commercial Items

[This section was updated for accuracy].

This part can be maddening. Despite regulations not requiring the submission of certified cost or pricing data for commercial items, some contracting officers still ask for, and even require it, to include many tiers of suppliers. The DoD expects its auditors to assess a company’s books to ensure it is getting a fair and reasonable price on commercial items. This is not how industry works or prefers to do business. DoD cannot expect to only consider production costs in the pricing model and ignore the millions or billions in R&D investments to get there. Industry should be able to offer the DoD a price for the product or service and the DoD can agree, negotiate, or reject that price. It’s not DoD’s decision to determine an acceptable profit margin of 7-10%. If a company can offer a solution at a lower price to the DoD than their competitors and have a 40% profit margin, great. DoD needs to train and empower its contracting officers to make sound business decisions, remove these restrictions, and arm them with market data. DCMA’s Commercial Item Group is a small resource within the DoD to support contracting officers with market- based price (not cost) analysis.

Investment in R&D vs Procurement

If you were given $300B and told to rapidly acquire capabilities for the warfighters, how much would you invest in research and development vs. procurement?

The DoD went from spending nearly three quarters of its investment funds in procurement to nearly a 50/50 split in the FY24 budget. At a time when industry is also spending more on R&D than DoD, when DoD leaders, Congress, and federal law drive a preference for commercial products and services, why is Congress and DoD spending such a large percentage on R&D?

While DoD executives champion production at scale, they cannot afford to execute on that plan. Leveraging the R&D funding the defense and commercial companies already invest to develop capabilities, DoD would be better positioned by shifting back to historical norms of investments to capitalize on American innovation. This would shift over $20B from RDT&E to Procurement, incentivize companies to offer DoD commercial solutions, and enable DoD to increase production and accelerate capability deliveries.

Opportunities

Shape Portfolios and Programs

Program Executive Officers (PEOs) are increasingly adopting capability portfolio management practices. This approach shifts focus from overseeing the execution of dozens of stovepipe acquisition programs to delivering an integrated suite of capabilities. Breaking down large acquisition programs into integrated capabilities enables greater opportunities to harness commercial products and services to complement new system development. The Atlantic Council’s Commission on Defense Innovation Adoption (which I am a co-author) outlined the opportunities for modern portfolio management in its interim report.

Engage Industry Prior to Formalizing Requirements

As part of the portfolio strategies, PEOs and their organizations must actively engage industry early and often. They must clearly convey their portfolio demand signals - the operational challenges they face and the capabilities they need. They must work with traditional and non-traditional defense companies to understand their current capabilities and what’s in their development pipeline. They must offer research and prototyping agreements to explore leveraging commercial solutions for their needs.

As the law requires, prior to developing formal requirements for an acquisition program (or ideally portfolio capability needs), DoD should engage industry on the capability needs. Solicit commercial products and services that could address these needs in whole or part. Acquisition leaders should involve operational commands and requirements organizations to be a part of industry engagements to foster direct, two-way communications.

For each requirements document, acquisition strategy, contract strategy, and review, one of the opening sections should explicitly answer the following questions:

Are there commercial services, products, or non-developmental items that can address some or all the capabilities needed?

What steps were taken to engage industry to identify and explore potential commercial solutions?

What trade space did you discover in speed of delivery, holistic costs, and performance in assessing commercial solutions vs new system development?

Preferences should be provided to programs and contractors who offer solutions that maximize the use of commercial products and services. This can be from part of the annual budget prioritization to source selection criteria. Lifecycle cost estimates should assess the benefits.

Work with Innovation Linchpins DIU and AFWERX

Organizations like the Defense Innovation Unit and AFWERX have led a growing defense innovation ecosystem to be on the forefront of engaging industry.

DIU was established in Silicon Valley and has since expanded to other tech hubs like Boston, Austin, and Chicago. They assembled an elite team with deep industry backgrounds who know the tech, the companies, and their environments to connect them with DoD opportunities. Even when their budgets were tight or cut, DIU awarded over $1.2B in agreements to harness commercial tech, leading to nearly $5B in follow-on production contracts to date. Similarly, DoD can leverage the many other transaction authority consortia with, many companies assembled around key technology or mission area opportunities.

House Defense Appropriations Committee Chairman Rep. Ken Calvert seeks to place a big bet on DIU. In their FY24 bill, they would fund DIU and related Service organizations a billion dollars for a hedge portfolio strategy. To significantly accelerate affordable fielding of critical joint capabilities in short order.

AFWERX leads the Air Force’s SBIR/STTR program which is the dominant adopter across the department. It works with hundreds/thousands of perspective vendors and DoD sponsors to award SBIR / STTR Phase I, II, and III contracts. This has provided seed funding to fuel many promising solutions and get many companies involved in defense markets. The challenge however is scaling the successful prototypes to become or integrate into programs of record. The Navy SBIR team appears to have enabled greater transition success by upfront matching with program offices.

Within the DoD, innovation hubs, chief technology officers, defense labs, research and development centers, universities, other transaction consortia, and acquisition organizations must improve collaboration around tech scouting. How many DoD organizations are out there today exploring AI, cyber, and autonomous solutions? How many vetted the same companies, products, or solutions? DoD needs to do a better job of sharing its due diligence on companies and solutions. This can save months and unlock countless opportunities that overworked acquisition professionals would have missed. There will not be a single centralized database, but more work is needed to align systems, processes, and culture for a federated model.

Navigate Rapid Acquisition Pathways

Urgent Operational Need (UON): Getting a Combatant Commander to put the capability need in writing and then sending it to the Pentagon to validate and identify funding. These capabilities must be delivered within two years. That requires mature technologies and often harnessing commercial solutions. A Service unique UON is going to be much more achievable and timelier than a Joint urgent or emerging operational need. The biggest challenge is identifying and reprogramming funding from existing programs to execute an approved UON.

Middle Tier of Acquisition: There are two sub-paths here, rapid prototyping and rapid fielding. If the commercial product is mature with “minimal development” and the production line can get up and running in six months, use rapid fielding. If you want to prototype a commercial solution to mature the tech and/or integrate into the defense environment, use rapid prototyping. These have five-year limits. This pathway is one of the best opportunities to rapidly acquire commercial solutions yet is under active sabotage by some in the Pentagon and Congressional staff.

Software Acquisition Pathway: This pathway, directed by Congress, is designed specifically to harness modern software development practices like Agile and DevSecOps. Given software is central to nearly every DoD mission, major system, and critical technology, the department now has a pathway to deliver software solutions rapidly and iteratively. As the war in Ukraine has demonstrated, software defined warfare is the future of conflict. This pathway will continue to grow in adoption to include commercial software, development pipelines, and services.

Apply Novel Contracting Strategies

Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO). A competitive process to obtain solutions or capabilities that fulfill requirements, close capability gaps, or provide potential technological advances. CSOs are like a broad agency announcement, yet may be used to acquire commercial items, technologies, or services that directly meet program requirements. DIU pioneered CSO use in the DoD through a Congressional pilot program that Congress recently made permanent. CSOs are limited to fixed price contract arrangements. CSOs over $100M require approval from the DoD or Service acquisition executive. CSOs may be used with other transaction authority.

Other Transaction Authority. While OTAs have been around for decades, the DoD drastically increased use of OTAs the last few years. These agreements are for research, prototyping, and/or production. They have greater speed and flexibility than traditional FAR contracts, which is invaluable to make it easier for nontraditional defense contractors to do business with the DoD. DoD continues to iterate on guidance and use of OT agreements, yet some fall back to adding traditional FAR clauses or mindset which reduce the impact. DoD can use an OT to rapidly prototype a commercial solution in a defense environment and if it proves to be successful can scale to production.

Unsolicited Proposals. The Federal Acquisition Regulation states “unsolicited proposals allow unique and innovative ideas or approaches that have been developed outside the Government to be made available to Government agencies for use in accomplishment of their missions. Unsolicited proposals are offered with the intent that the Government will enter into a contract with the offeror for R&D or other efforts supporting the Government mission, and often represent a substantial investment of time and effort by the offeror.” Companies with viable commercial solutions should consider providing the DoD unsolicited proposals to potentially fast track opportunities.

FAR Part 12, Commercial Items. This section is explicitly for commercial products and services. This enables the DoD to use commercial market pricing, reduces time and costs with streamlined procedures and terms and conditions. This requires a commercial item determination and a firm fixed price or term and materials contract. Furthermore, within DoD, supplies and services from non-traditional defense contractors (NTDC) are considered commercial items. The statutory criteria to be an NTDC is an entity not currently or within the last year been a part of a DoD contract subject to the cost accounting standards.

FAR Part 13, Simplified Acquisition. This section also provides for streamlined processes to acquire supplies and services including R&D and commercial items. This includes Blanket Purchase Agreements and purchase orders for open market supplies and services below $250K, but for Commercial Items up to $7.5M.

R&D Agreements. Separate from FAR contracts and OTAs, there are a few other formal agreements the DoD and companies can establish for R&D and procurement. These include a cooperative research and development agreement (CRADA) whereby the DoD and a contractor share technologies, ranges, and test data at no cost to the DoD. Procurement for experimentation authorizes DoD to acquire quantities of a product necessary for experimentation, technical evaluation, and assessment of operational utility, or to maintain a residual operational capability in nine technology areas. DoD can use these to collaboratively research, develop, and experiment with commercial solutions in a defense environment.

Technical Standards

Integrating a wide array of technologies from competing companies has been a perennial challenge. Many seek to offer closed, proprietary systems to ensure lock-in bargaining power and protect longer-term sustainment and upgrade revenues. Congress made modular open systems approach the default practice in statute, yet DoD has struggled for decades to implement broadly. DoD should harness commercial standards, protocols, and services to the maximum extent practicable. When unable to, it should collaboratively work with industry to co-develop common standards and interfaces for the defense environment. This enables more companies to offer solutions that can easily integrate with the broader capability suite. This will drive greater cybersecurity and interoperability across the Joint Force and with allies and partners. Cybersecurity must be baked in upfront, central throughout development and test, and a daily consideration throughout operations. DoD must also strike the right balance on intellectual property and data rights based on the specific market conditions. DoD should seek to own the technical baseline for the key interfaces, then enable industry to do their thing.

Leadership Direction and Top Cover

Leadership at all levels and across acquisition, requirements, budget domains, must clearly and regularly communicate the demand and expectations to harness commercial solutions. A common set of talking points can reinforce speed of delivery of capabilities to the warfighters, fueling novel, disruptive solutions that the traditional model would have never come up with, rebuilding and expanding the defense industrial base to exploit America’s leading tech companies, cost efficiencies leveraging commercial markets, and greater interoperability across the Joint Force and allies. Leaders must regularly ask acquisition programs how they’re harnessing commercial solutions and reinforce that is the default model to start with. It must provide top cover to acquisition professionals and programs that lean forward to explore commercial solutions, even if some fail.

Commercial Guidance, Training, and Workforce Incentives

The acquisition executives must assemble a team to iterate and scale the guidance and training around commercial acquisition. It should seek to arm acquisition professionals across the six major disciplines on commercial considerations with clear how-to guidance. This guidance should be published online in a dynamic digital format, not a 100+ page PDF, and continuously improved with inputs and use cases (positive and negative) from across the workforce and industry.

Training on commercial acquisition should be scaled across DAU, NDU’s Eisenhower School, and the Service unique universities. It should be tightly aligned with the guidance and include more hands-on workshops and webinars to discuss current commercial solution examples and challenges.

Finally, the workforce must continue to be incentivized to harness commercial solutions. Valuing speed of delivery, growing the industrial base, and acquiring novel solutions for the warfighter should be regularly reinforced. There could be commercial acquisition awards at the department, Service, and local levels as well as selecting those who successfully harnessed commercial solutions for the existing acquisition awards.

As someone who has spent over 25 years in defense acquisition, the drive has always been to rapidly deliver the best capabilities to the warfighters to accomplish their missions. Acquisition professionals don’t want to spend a 3–4-year tour simply advancing a massive program from one milestone to another with dozens of strategy documents and reviews. Imagine the engagement and impact of rapidly prototyping and experimenting with commercial and defense technologies with the operators, then rapidly scaling and integrating the proven capabilities to deliver solutions. Remember, the more time the bureaucracy takes to “burn down risk”, they simply transfer that risk to operators who are working with 30-year old legacy systems in an increasingly hostile global environment.

DoD must buy commercial solutions for national security to deter China this decade.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.