Funding Defense Research vs Production

Investing in capabilities for the next five years or the next decade.

Mislav Tolusic published a piece Why DoD Should Get Out of the R&D Business.

He makes the case that DOD R&D funds “incremental improvements, not revolutionary changes”. Instead of Defense R&D, “the DOD should tap into the strong investor interest in dual-use technologies and the record amount of venture capital waiting to be deployed.”

This is consistent with Mike Brown’s Fast Follower strategy where he stresses DoD should rapidly adopt commercial technologies. Of DOD CTO’s 14 critical technology areas, 11 are commercially driven.

That prompted an examination of defense budget trends. Thanks to Eric Lofgren for the historical budget data.

In FY23, Congress appropriated $140B in RDT&E and $162B in Procurement. This was hyped by DoD and Congress as a significant surge to critical weapon system investments. The disappointing point is that nearly half (46%) of the surge is allocated to RDT&E, which does not provide our warfighters with the capabilities it needs for tomorrow’s fight.

The trend of splitting investment accounts between procurement and R&D is a relatively new one. For the last 40 years, the allocation has been dramatically in favor of procurement. It’s only the last decade where R&D has gained such parity with procurement.

The trend really started in FY17, with a major jump in FY20 and continued the last few years. The FY23 President’s Budget Request was 47% RDT&E, yet adjusted after $26B in additional Congressional appropriations for investment accounts.

If FY23 was funded in line with historical ratios, the defense budget would be closer to $118B RDT&E and $184B Procurement.

That would be a $22B shift toward procurement.

As the National Defense Strategy, DoD leaders, and Congress continue to stress the need for production at scale and rapid delivery of capabilities to deter China in the IndoPacific within the next five years and replenish inventories provided to Ukraine, $22B of additional procurement funds would come in handy right about now.

That funding would also expand opportunities to tap leading technologies from startups, scale-ups, and other non-traditional defense contractors. This lack of procurement focus is what led them to plea with President Biden when he took office. The existence of $22B in potential production contracts would provide a greater incentive for startups to pursue private investment to solve DoD challenges than current small dollar SBIR awards or prototypes.

With 79 Middle Tier of Acquisition rapid prototyping programs underway, a larger procurement budget can also help rapidly scale those efforts.

This recommendation comports with AEI’s John Ferrari case that DoD should move $45B each year for the next five years from R&D into procurement. Mackenzie Eaglen made a similar case for capacity to address the brittle force: “A healthy and feasible ratio is closer to 2.25 to 1. To meet the threat from China, policymakers should shift $45 billion per annum from research and development into procurement over the next five years.”

Given the time urgency for China/Taiwan, replenishing our depleted inventories, and the increased leveraging of commercial technology R&D, a bolder shift to procurement makes sense.

While this is much easier said than done, when unpacking the RDT&E accounts, we can see some of the rationale. The waves between RDT&E vs Procurement is in part due to the timing of initiating many major weapon systems. With the full funding statute in place for MDAPs (and now MTA programs), and many large dollar major programs recently initiating R&D, they consume a significant % of RDT&E budget.

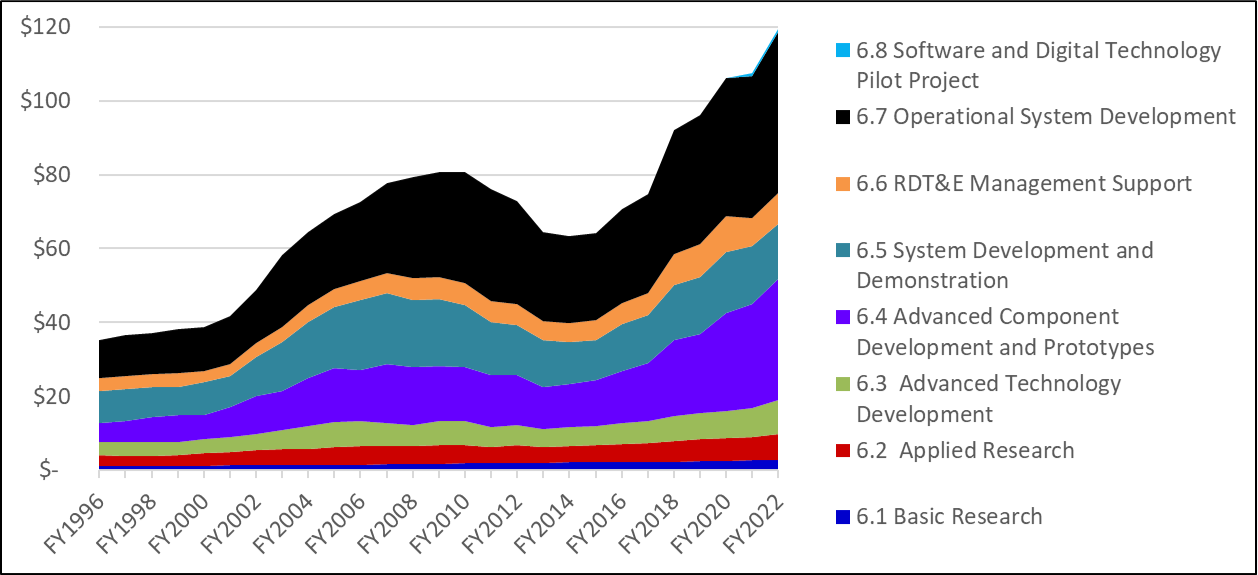

In examining the RDT&E breakouts (above graph) by budget activity, the recent growth is in 6.4 accounts for advanced component development and prototypes, which can be helpful in tech transition to cross the Valley of Death and militarizing commercial solutions.

The other major and growing area is in 6.7 Operational System Development to upgrade fielded systems. The majority of 6.7 is classified, which notionally addresses high operational priorities and/or groundbreaking technologies. An ongoing debate is whether DoD should upgrade 30-year old legacy systems or regularly produce new versions. Significant upgrades are still being planned for legacy platforms such as the F-15E, AWACS, F-16, RQ-4, and B-2.

While not a major slice of the RDT&E budget, S&T accounts have also been rising. An issue that does not get much debate is how much of the DoD budget should be allocated to basic and applied research. A holistic view of federal R&D and industry R&D (defense prime IRAD and commercial) is needed to shape DoD research budgets.

As DoD finalizes the FY24 budget and begins planning and programming for future FY budgets, they should seek to pivot tens of billions from RDT&E to procurement. DoD requires scaled capability production at scale and accelerated deliveries to INDOPACOM in the fast approaching Davidson window.

Really interesting. I wonder if part of the necessary shift is also how some of the financial regulations are interpreted. Some programs (🙋🏼♀️) have done great innovative things without RDT&E. The Department is making some progress in that mindset with the pilot for a unique appropriation for software because too many finance officers could not comprehend that software requires continuous “development.” I think that how we define items that require RDT&E funding could change this landscape significantly. But now we’re talking about regulatory change AND culture change and neither are fast processes. I think we need to start though.

you are putting out some great stuff!