SAC-D FY24 Defense Appropriations Summary

Acquisition and Budget Reforms along with Special Interest Items

The Senate Appropriations - Defense Subcommittee (SAC-D) released their FY24 Defense Appropriations bill last week. This is the first of a two part summary.

These are the key areas…and our takeaways based on the tone and content of the congressional language.

PPBE Reform: Will not relax controls for more DoD fiscal mismanagement.

Innovation: Sound fiscal management and adherence to cost and schedule.

MTA and OTA: Have every corner of the Pentagon certify your rapid effort.

Multiyear Procurement: Negotiate better to achieve EOQ cost savings.

JADC2: Consolidate PEs for better oversight of inadequate acquisition strategy.

Loans: OSC is unexecutable because DoD didn’t formally request authorities.

Defense Industrial Base: More data driven analysis of your supplier base.

Our second part will go into more detail into program budgets.

The language throughout the bill communicates a willingness to work with the DoD on various initiatives, but then declines most of the department’s requests, citing past failures or other ways that the committee has funded DoD efforts.

Italicized language represents the congressional language in the report.

PPBE Reform

The Committee is aware of proposals that seek to modify the DoD PPBE process, including by relaxing financial controls and oversight mechanisms that were put in place as the result of previous instances of financial mismanagement, unacceptable cost growth, or the expenditure of resources that more prudently applied would likely have led to capabilities fielded sooner than the unrealistic timeframes set for many of these programs.

Our Take: This opening paragraph tells you all you need to know about SAC-D’s receptivity to meaningful PPBE reform. They clearly see the current system as functioning appropriately despite the desperate calls from many for reform.

At a time when the Department’s financial statement audits continue to result in disclaimers of opinion, caution is in order to relax financial controls put in place as corrective actions to past systemic failures.

Our Take: It’s a continuing red herring by some on the Hill to throw audit results (which are accounting exercises) as some indication of DoD financial malfeasance. The audit failures are more a result of outdated IT systems.

In addition to submitting reprogrammings for congressional review on a near-monthly basis, the DoD submits a large, mid-year omnibus reprogramming action each year that proposes to realign billions of dollars across dozen of programs.

Our Take: They note that from FY20-22, their committee processed 10 of the 11 reprogramming packages quickly and approved 25 of 39 reprogramming new starts. What was not talked about was that congressional processing resulted in ~40 changes to DoD’s FY22 Omnibus reprogramming request - seriously reducing it from its original scope. See for yourself.

Granting the DoD blanket authority to establish new starts outside of the traditional budget review cycle would undermine the constitutional authority of the Congress regarding the expenditure of taxpayer funds.

Rejecting the SECAF’s proposal on constitutional grounds is simply hyperbole. It fails to mention that up until 2000, certain actions (like a new start) had only required congressional notification…which was changed to require prior approval from all four congressional committees. See Eric Lofgren’s run-down.

Paraphrase: GAO found that DoD rarely uses the full extent of its General Transfer Authority (GTA), which is the ability to move funds from one appropriation to another, and has only done so once in the last 12 years (2012). In some years (2014-2017), it used less than 50% of its GTA. To date for FY23, DoD is only using 34% of its $6B allotment.

Our Take: This is not meaningful data. Reprogrammings are constrained by the availability of “good sources” with which to fund new requirements. A good source is one where DoD can demonstrate its use will not cause any major impacts to other program lines. This is a high bar and there is much internal deliberation before a source is put forward on an ATR. Sources that DoD knows Congress will deny are not even offered. Not fully using GTA is more attributed to that reality than DoD purposefully not exercising its flexibilities.

Recognizing that long-established reprogramming thresholds have not kept pace with the growing cost of doing business, and to further address concerns about funding flexibility, the Committee recommends increasing the prior approval reprogramming thresholds for certain O&M activities and the acquisition accounts, as detailed elsewhere in this report.

Our Take: It is a positive sign that Below Threshold Reprogramming limits are being officially recognized as outdated. The Section 809 Panel called out this fact 4 years ago and other reports in recent years have echoed that finding. Since DoD cannot unilaterally raise them (that requires appropriation bill language), it would have been more helpful for SAC-D to adopt figures put forward in previously referenced reports in this bill. It appears to only be signaling support.

In support of the Department of the Army’s Modernization Strategy, the congressional defense committees enacted budget line item consolidations in FY20. The Committee notes this consolidation supported or fully funded 31 modernization programs, eliminated 93 programs, and truncated 93 programs. The Committee includes direction this year to the Army to study proposals for further budget line consolidation within Other Procurement, Army account.

Our Take: Any steps to consolidate budget lines is a positive one. The Army should identify areas and negotiate with appropriators to gain more flexibility. However, focusing on Other Procurement is likely to be low impact. The Army’s FY24 request was only for $1.2B. Over 30% of that was for the JLTV. Support equipment and spares make up for most of the other funding. It is ripe for consolidation. 76 of the 80 budget lines are less than $50M, with some as small as $68,000.

The Committee notes that the DoD’s PPBE process is currently under review by an independent Commission established by Congress. The Committee looks forward to reviewing the recommendations of the Commission backed by clear, measurable outcomes or quantitative data. The Committee looks forward to continuing partnering with the DoD, the defense industrial base, and other stakeholders to strike the proper balance of flexibility, accountability, and oversight in resourcing our National defense.

Our Take: Its yet unclear how bold the PPBE Commission will be in its reform recommendations but the bolded statement above is coded language that sets a very high bar for any proposed significant changes the Commission might make.

No changes shall be made to the appropriations structure with submission of the President’s FY25 budget request without prior consultation of the defense appropriations committees.

Our Take: This is preemptive language to discourage DoD from submitting a budget that deviates from the agreed-upon structure. Its unlikely DoD (or OMB) would do this anyway, given its inherent conservatism.

Innovation

The Committee shares the view that the DoD can speed up acquisition timelines to execute critical acquisition programs. However, the end goal of acquisition must remain to field the most advanced capabilities to the warfighter at scale, thereby strengthening our Nation’s defense. Many of the controls and oversight mechanisms in place within statute and regulation are the result of previous instances of financial or acquisition mismanagement, unacceptable cost growth, or wasteful acquisition strategies that delayed fielding timeframes for programs.

Our Take: While DoD has had some failures, this is a gross overstatement for justifying tighter congressional control than in past years. No one should operate under the pretense that military tech development and fielding is not a risky business. The acquisition system is burdened with many rules and restrictions that contribute to this risk.

Therefore, it is imperative that speed and innovation do not come at the expense of sound financial, acquisition, and management best practices essential to delivering capability to the warfighter on time and on budget.

Our Take: The focus on time and budget is disappointing as they are merely projections early in the project rather than focusing on speed of delivery and mission impact. Warfighters are operating with 30-year old legacy systems. The bureaucracy has struggled to deliver any meaningful capabilities at scale in under a decade…despite meeting cost and schedule baselines.

The Committee recommends substantial resources to the DoD for flexible, innovation-focused spending, including more than $1.2B for the military services and for department-wide transition funds that promote the prototyping and maturation of promising, early-stage, and commercial capabilities. It also notes that DoD’s annual budget for SBIR/STTR programs is approximately $2B annually and continues to offer a key and underutilized pathway to fund innovative and promising technologies.

Our Take: This is clearly a response to the HAC-D proposal to establish a hedge fund run by DIU. The report references a number of “innovation accounts” such as the Army’s Technical Maturation Initiative, the Air Force’s Future AF Integrated Technology Demo PE, the Navy’s Innovative Naval Prototype account and the USMC’s Advanced Technology Demonstration PEs. While these are substantial accounts, they are not unaccounted for funds. Instead, they constitute a multitude of smaller technology projects planned for in advance and accounted for in the budget docs. Interestingly, despite the purported support, the above Air Force and Army accounts were hit with a 20% - 25% reduction by SAC-D.

RDER

In addition to these innovation funds, the DoD continues to request funding for activities under the auspices of the Rapid Defense Experimentation Reserve [RDER]. The Committee is supportive of the development of joint capabilities that can be successfully fielded and integrated at scale. However, the Committee remains concerned that production, fielding, and sustainment of resources for successful RDER projects have not been fully budgeted for within the FYDP. Therefore, the Committee continues to fund innovative, experimental activities of this nature through the military service technology transition funds, as detailed above.

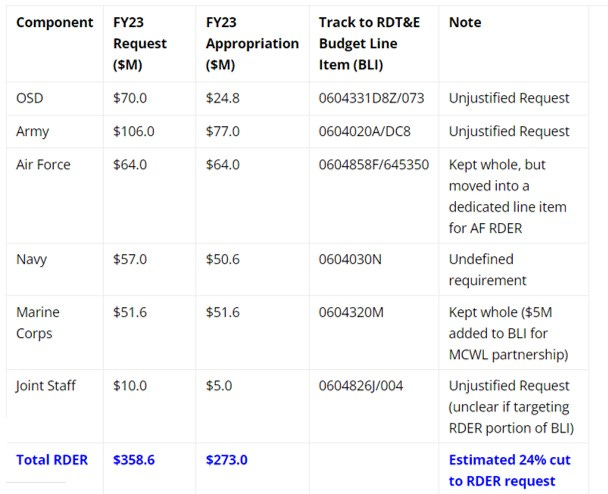

Our Take: The irony is strong here given that Congress cut the funding allocated to the FY23 RDER projects in Service accounts by ~24% (see table below and here). Regardless, it is poor justification to cut RDER funding because of a future potential shortfall that can be resolved by adding funds to those accounts this year or in future budgets. If there’s a problem, fix it. This is clearly prejudice towards flexible accounts. In the detailed SAC-D marks, RDER was slashed nearly 60%.

Additionally, to further enhance the DoD’s ability to tap into innovative commercial solutions, the Committee recommends $20M to support the Advanced Defense Capabilities Pilot program that will enable a public-private partnership to make loans and loan guarantees in partnership with the DoD for the first time. The Committee notes that this recommendation is in addition to DOD’s expansive existing authorities, including those provided via the Defense Production Act, which enable the DoD to directly invest in capabilities critical to the National defense, including through the provision of loans and loan guarantees.

Our Take: Allocating $20M to tap into commercial solutions to solve the weighty problems that DoD faces is hard to view seriously. The HAC-D proposed over $1B for the much-needed DIU hedge fund. That was a serious proposal and one that SAC-D should join in at conference.

Innovation Organizations

The Committee is concerned that, in an effort to create and harness innovative concepts, acquisition authority is becoming overly dispersed horizontally to DoD organizations such as DARPA, DIU, SCO, and the OUSD(R&E). This dispersal has the potential to degrade the DAE and SAEs ability to exercise their statutory responsibilities, and dilutes meaningful acquisition leadership. The Committee continues to believe that the vertical delegation of acquisition authority down the chain-of-command from the DAE to SAEs and SAE designees has, in general, resulted in faster and more sound decision-making and acquisition outcomes. This reduces bureaucratic barriers and enables innovative investment decisions through closer collaboration among the individuals responsible for requirements, acquisition, sustainment, and most importantly operational employment.

Our Take: We have always been advocates of delegating authority down to lower levels so very supportive of that notion…hence our advocacy for more funding flexibility for PMs and PEOs. However, the response here is clearly related to the efforts of other defense committees to provide more authority and budget to OSD-level organizations. There is a role for DARPA, DIU, SCO, R&E and the Services to play in building a joint force especially given the threats we face today.

Innovation Authorities

It is the Committee’s position that ample authorities exist to enable these organizations to adopt innovative and agile acquisition practices, but that DoD has underutilized many of them. A June 2023 GAO report found that Congress provided DoD at least 26 new authorities to increase flexibility in R&D, innovation, and modernization activities from FY17 to FY21.

For example, OTA provides the DoD the authority to enter into non-traditional transactions in support of R&D, deployment and even-follow-on production projects.

Rapid Acquisition Authority [RAA] allows the DoD the use of $650M annually to fund higher priority requirements in support of urgent operational needs without requiring a reprogramming action. However, over the last 3 years, only $84M of the $1.95B in RAA authority has been utilized.

The rise of the Adaptive Acquisition Pathway and other flexible acquisition authorities have also continued to offer numerous avenues for prototypes funded through the above-mentioned flexible funds to graduate to programs-of-record, leading to the fielding of capabilities at scale. Finally, the Middle Tier of Acquisition authority [MTA] provides the Department with 5-year periods to rapidly develop and/or field prototypes that incorporate proven commercial technologies and require minimal development.

Our Take: Unclear what SAC-D’s point is here on DoD not fully using its innovation authorities. DoD continues to use OTA and MTA authorities, yet face huge resistance from the committee in using them. See below.

As for RAA, the reason for its limited use is the significant programmatic and financial management burdens placed on the budget accounts RAAs are sourced from…which discourages broader application.

The Committee believes that the DoD must be clear-eyed that utilizing innovative or rapid acquisition authorities carries inherent acquisition risk to cost, schedule, and performance.

[They then cite three MTA and JEON programs, Air Force ARRW, Navy’s XLUUV, and Army’s ERCA noting significant cost and schedule overruns. ]

The Committee notes that these examples do not necessarily mean that MTAs are an inappropriate tool for fielding capability, but they each points to the need to understand requirements, technical risk, systems engineering, and the industrial base capabilities upfront before pursuing this acquisition path.

When appropriate, the Committee will continue to support recommendations to further enhance innovation that advances the Nation’s defense while balancing risk and opportunity.

The Committee directs the SAE of each of the military Services to provide Congress a report that details processes and authorities used to ‘‘pull’’ innovation from the various innovation organizations within the Department. Further, that report shall detail procedural or budgetary obstacles to further enhancing the integration of the above-described entities and efforts.

Our Take: SAC-D has been hostile to MTA since it was established. Each year it imposes additional burdens on MTA programs to make it harder to use. With any new major initiative, there are bound to be mistakes early in adoption. Similarly, had these programs used the traditional 10+ year acquisition pathway, it does not mean that it would have achieved greater cost, schedule, or performance success. Any acquisition requires sound program strategies and execution. Furthermore, with rapid prototyping programs, one should expect a higher failure rate, so long as they are accelerating learning for designing and delivering feasible capabilities to the warfighters.

Reporting on Mid-Tier Acquisition and Rapid Prototyping Programs.

The Committee remains supportive of efforts to accelerate the delivery of capability to the warfighter, including through the use of rapid acquisition authorities and contracting strategies provided in existing law, such as the middle-tier acquisition (‘‘section 804’’) of warfighter capabilities. As in prior years, the Committee directs the USD(R&E) and USD(A&S), in coordination with the SAEs to provide Congress with submission of the FY25 President’s budget request a complete list of approved acquisition programs, and programs pending approval in FY25, utilizing prototyping or accelerated acquisition authorities, the rationale for each selected acquisition strategy, and a cost estimate and contracting strategy for each such program.

Our Take: We are confused how the appropriation staff became the Acquisition Decision Authority for all MTA programs. This level of information is not provided to Congress for even the largest MDAP programs. To use the words “remain supportive” is a proverbial slap in the face to those who have fought to preserve this much needed acquisition authority.

For Context: A few years ago, Congress directed OSD (then AT&L, now A&S) to delegate decision authority for all but a handful of MDAP programs to the SAEs. This was done because it was perceived that acquisition decisions were not improved as a result of being elevated. SAC-D would seem to support this point since it noted in this report, that vertical delegation results “in faster and more sound decision-making and acquisition outcomes.” Yet they simultaneously question every decision of those acquisition leaders when it comes to the MTA pathway.

If you thought that was all…don’t worry there’s more!

Further, the DoD and Service Comptrollers are directed to certify full funding of the acquisition strategies for each of these programs in the FY25 President’s budget request, including their test strategies;

Historically, this was only required for MDAP programs (see 10 USC 2366).

Finally, the DOT&E, is directed to certify to the congressional defense committees the appropriateness of the services’ planned test strategies for such programs, to include a risk assessment.

Historically, this level of involvement from DOT&E was only required for programs on the DOT&E oversight list.

Further, the Committee directs the USD (I&S) to certify to the congressional defense committees that the services have conducted a valid lifecycle threat review.

This is a novel requirement and not an insubstantial one given the significant lag that can occur when requesting acquisition intelligence products. Keep in mind, this is assessing lifecycle threats for rapid prototypes and production efforts.

To the extent that the respective SAEs, service financial manager and comptrollers, and DOT&E, provided the information requested above with submission of the FY24 President’s budget, any variations thereto should be included with the FY25 submission.

Can only read this as “the pain will continue for MTA programs.”

In addition, the services’ financial manager and comptrollers are directed to identify the full costs for prototyping units by individual item in the RDT&E budget exhibits for the budget year as well as the FYDP.

The whole concept of the MTA pathway was to learn during prototyping and allow that to influence requirements i.e. they may be relaxed in areas that are deemed too risky (like the ERCA program). It is hard to cost a prototype without a hardware baseline established. Prototype units are most often more expensive than they would be off an established production line so the relevance of this information is unclear for purposes of the MTA prototype effort.

Our Bottom Line Take: SAC-D seems likely to continue throwing hurdles onto the MTA pathway to discourage its use. If they were truly supportive, why would it have every corner of the Pentagon certify and report to Congress at a level that exceeds MDAP burdens? Particularly, since MTA was created as a rapid alternative to the MDAP bureaucracy in light of the China threat (RIP Sen McCain).

Other Transaction Agreements (OTA).

The Committee notes the continued importance of this reporting requirement, particularly given the increased use of consortia to facilitate OTAs and difficulty in readily identifying the actual performing vendor.

The challenge in identifying the vendor only relates to external stakeholders. Agreement Officers executing OTs through a consortia are privy to that information.

The Committee encourages the USD(A&S) to monitor the services individual utilization rates of OTAs and ensure that the guidance surrounding their use is consistent across the services.

Unclear why utilization rates need to be monitored. Is there an arbitrary threshold that can be tripped re: OT usage?

The Committee directs the USD(A&S), not later than 60 days following enactment of this act, to submit a report to the congressional defense committees on the DoD’s use of OTA agreements in FY23, to include an analysis of the relative success rates of follow-on production contracts initiated after the conclusion of initial OTA agreements in comparison to lessons learned from conventional FAR-based acquisitions.

We support providing Congress insight into the effectiveness of OTs since they granted that authority and deserve after-action analysis. The comparison to FAR contracts however is nonsensical since the FAR does not provide for follow-on procurement without additional competition.

In addition, the report shall include an appendix that identifies the policy for financial reporting of OTAs with specifics on the data collection requirements.

Our Take: SAC-D appropriators appear to be showing a bias for using FAR-based contracts with increased reporting, oversight, and scrutiny on OTs that will only discourage increased use.

Multi Year Procurement (MYP)

The Committee notes that the FY24 President’s budget requests this authority (MYP) for seven weapons programs. The Committee recommends providing this authority for all requested programs with sufficient funding to allow the DoD to negotiate those proposed agreements and associated economic order quantities to ensure timely delivery of weapons at reduced costs.

However, the Committee notes that in some cases, the DoD is requesting funding to increase production capacity well above what is required by the proposed multi-year contract without firm private sector coinvestment commitments. The Committee believes that greater and more consistent industry co-investment is warranted to more equitably share both the costs and benefits of stable, multi-year procurement contracts.

Accordingly, in light of such disparities in funding strategies, and to encourage greater industry co-investment, the Committee recommends adjustments to facilitization investments. The Committee directs the Department to negotiate multi-year procurement contracts which yield unit cost savings commensurate with the stabilizing effect of economic order quantities, and industry commitments in facilitization with a particular focus on subcontractors in line with best practices including the ongoing approach to the VIRGINIA and COLUMBIA-class, as well as other shipbuilding programs.

The Committee further directs SECDEF to provide reports on each munitions multi-year procurement award on a semi-annual basis until all such munitions have been delivered, to include projected and realized cost savings; impact of government and industry investment on capacity and associated supply chain, identifying potential risks and weaknesses; and analysis of whether the multi-year procurement has created stability in the supply chain.

Our Take: For clarity, the MYP requested in the FY24 budget was for some critical munitions such as Naval Strike Missile, RIM-174 Standard Missile, Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile, Long Range Anti-Ship Missile and Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile - Extended Range. SAC-D approved EOQ funding but did take some serious marks against JAASM (-$77M for facilitization) and Standard Missile (-$100M for production early to need).

Separately, the HAC-D denied EOQ funding and slashed the Standard Missile funding line for “stabilize production ramp.” It remains unclear how industry becomes more incentivized to invest in facilitization when Congress cuts the funds that would have demonstrated a firm commitment. #mystery

JADC2

The DoD has identified the development of Joint All-Domain Command and Control [JADC2] as one of its highest priorities, noting that improved Joint Force C2 will lead to more coordinated and effective outcomes. The DoD’s ‘‘Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control Strategy’’ identifies five lines-of-effort, as well as a JADC2 cross-functional team as key enablers in the implementation of its JADC2 strategy.

The Committee acknowledges that development of a true Joint Force C2 system is an inherently complex task, requiring the coordination of the military services, combatant commands, and defense agencies.

While the Committee commends the DoD for achieving progress in the requirements definition process, it remains concerned that the DoD has not placed adequate emphasis on the acquisition and resourcing strategy associated with this effort.

In some instances, the DoD has described the Joint Fires Network as a near-term solution, and the work of the JADC2 cross-functional team to be focused on enduring outcomes. Additionally, the Navy’s Project Overmatch, the Army’s Project Convergence, and the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System are service-led initiatives in pursuit of outcomes similar to those of JADC2.

It is the Committee’s position that these investments should be mutually reinforcing, adequately balancing the need for immediate outcomes with sustainable long-term architectures, and retaining focus on delivering capability to the warfighter.

The Committee finds the current funding structure for Defense-Wide JADC2-related investments to be diffuse, limiting oversight entities’ ability to clearly identify what discrete activities comprise JADC2 related work, and which officials are responsible for achieving the goals outlined in the Department’s JADC2 strategy.

Therefore, the Committee recommends centralizing all Defense-Wide JADC2 resources and Joint Fires Network resources into a consolidated Program Element to increase unity of effort, traceability, and accountability.

Consolidating JADC2 PEs at the defense-wide level would not provide a meaningful effect since neither JADC2 nor JFN has a dedicated funding source.

Further, the Committee directs the SECDEF to deliver a report to the congressional defense committees, not later than 90 days after the enactment of this act, that identifies a single acquisition executive responsible and accountable for the development and implementation of JADC2, provides a resourcing and programming strategy for investment in common enterprise-level JADC2 capabilities across the FYDP, and establishes a framework for prioritizing near-term versus long-term capability developments.

In addition, following the delivery of this report, the SECDEF is directed to brief the congressional defense committees semi-annually on the Department’s progress in implementing the topics included in the aforementioned report.

Our Take: While a single acquisition executive to oversee (not execute) JADC2 may be a worthy course of action, the intent here seems to be focused on traceability of funds and not necessarily improved effectiveness at delivering JADC2 capability. Given how much investment is already underway across multiple organizations, any centralization would be extremely disruptive to those teams. A better COA is to request details on the architecture that allows all the disparate pieces across the Services to coalesce into a joint capability.

Loans and Loan Guarantee

The FY24 President’s budget request includes $99M for the Office of Strategic Capital [OSC]. The Committee notes that a portion of this funding is intended to support a loan guarantee program that supports investment in companies pursuing critical technologies of interest to the DoD. The Committee supports the use of existing loan, loan guarantee, and other authorities available to the DoD pursuant to 50 USC Chapter 55.

The Committee is concerned that the Administration has not formally requested new authorities for OSC that would allow for the requested funds to be executed. A formal request of this authority is essential to understand how Government-issued loans and loan guarantees would be implemented, particularly as such actions could require actions by Government entities other than the DoD.

Therefore, the Committee views the funding requested within the President’s budget request for OSC as unexecutable.

In contrast, the Committee notes the FY24 NDAA, as reported by the SASC, would authorize an Advanced Defense Capabilities Pilot program. This provision establishes a public-private partnership to provide financial support to companies in the defense industrial base based on guidelines from the USD(A&S).

The public-private partnership model limits direct government involvement in the administration of the program, which manages the risk to the Government.

In particular, the provision requires the public private partnership to invest in not less than 10 businesses, with no businesses representing more than 20% of the partnerships’ total investment.

Moreover, such an arrangement would allow the public-private partnership to draw on the past successes of In-Q–Tel, which the Committee notes has delivered meaningful results to the United States and its allies for more than two decades.

Additionally, the Advanced Defense Capabilities Pilot distinguishes itself from other innovation proposals by focusing investments on strengthening domestic defense supply chain resilience and manufacturing, which the Committee deems to be of urgent concern.

Therefore, the Committee recommends $20M only for the Advanced Defense Capabilities Pilot, as authorized in section 831 of S.2226, which is to be administered by the Office of the USD(A&S).

Our Take: The Office of Strategic Capital seeks to better align critical technology development with the capital required to deliver defense solutions at scale. The tone of this, consistent with the rest of the bill, shows hostility to SECDEF’s OSC efforts. Given most of the critical technologies identified by DoD’s CTO are commercially driven, OSC is designed to “crowd-in” tens/hundreds of billions in private capital to boost national security.

The Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain

The Committee notes that the FY24 President’s budget request includes investments to increase the capacity and capability of the Nation’s defense industrial base, particularly with respect to critical munitions.

While the Committee notes the work that the DoD has done to increase focus and attention to this matter, the Committee believes that additional work remains to empower a resilient and responsive defense industrial base.

The Committee continues to encourage the DoD to develop and adhere to a FYDP that provides stability and predictability to the defense industrial base.

Consistent and transparent budget projections enable the industrial base to better support the DOD’s requirements, including improving acquisition outcomes.

Additionally, the Committee notes the importance of fostering healthy competition within the defense industrial base.

The Committee believes that the DoD would benefit from additional data-driven analysis that identifies discrete sources of supply chain fragility.

The Committee is concerned that the DoD lacks visibility into the supplier base of many key programs, limiting its ability to target investments to smaller suppliers that simultaneously support multiple key defense programs.

This analysis should inform DoD investments at the sub-tier supplier level, which has the potential to drive efficiencies within multiple production lines.

The Committee remains committed to engaging with the DoD in order to promote a resilient and responsive defense industrial base.

Our Take: Supply chain risk is a top issue the DoD, the White House, and prime contractors are actively managing. More work is always needed in this space. There is however a limit to sub-tier supplier level visibility by DoD or primes given the proprietary contractual relationships.

Force Design 2030

The Committee strongly supports Force Design 2030 and appreciates the commitment of the Commandant of the Marine Corps to carry through with this plan and sufficiently resource the transition.

Our Take: Great to see support of Force Design 2030 including adding $500M for LPD amphibious ships.

With regards to "The challenge in identifying the vendor only relates to external stakeholders. Agreement Officers executing OTs through a consortia are privy to that information."

I would argue that this is true, but external stakeholders are important here. It's hard to evaluate the potentially quite positive role OTAs are playing for the industrial base when the reported prime doesn't provide visibility beyond the consortium level. The Agreement Officers have key information they need, but it's not their job to track across the enterprise. Apparently reporting systems are part of the problem here, but I think this is a challenge worth the attention to solve.