Modernizing Defense Requirements for the 21st Century

A 12 Point Plan to Implement a New Joint Requirements System

The Need for Reform

With Combatant Commands desperately waiting for capabilities that are still many years out and new commercial entrants into DoD left struggling to keep the lights on while they await DoD contracts, it is clear there is a disconnect between available solutions and unmet user needs.

In recent years, there has been extensive literature written on the need to reform defense acquisition as part of that disconnect. These discussions often focus on the use of novel acquisition approaches, flexible contracting strategies, improved technology transition, leveraging private capital and co-developing with our allies among others. There have been several commissions focused on solving this including the Section 809 Panel, the National Security Commission on AI, the Atlantic Council Commission on Defense Innovation Adoption, the Defense Business Board and the Defense Innovation Board.

Budget reform had a dedicated body in the Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution Reform Commission that developed detailed options for reimagining how we budget for defense (interestingly that same commission noted that requirements reform was critical for full PPBE reform).

Those reforms are all needed and will be very impactful for DoD in its pursuit of procuring innovative solutions. However, the requirements process remains a major obstacle to DoD’s goals on par with PPBE and Acquisition/Contracting challenges.

However, reform in this area has received little attention and only written about in pockets. The MITRE Corporation (shout out to Pete) published a very thoughtful piece a few years ago. More recently, the Acquisition Innovation Research Center proposed some reforms. Congress included provisions in the FY21 NDAA and FY24 NDAA for the Department to analyze factors driving long approval timelines and develop a more streamlined process. However, most of these efforts focused on maintaining the existing processes in a different form or elevating requirements to a more summary level.

We posit instead that the current requirements process (titled Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System - JCIDS at the Joint Staff level but replicated at the Service level) is fundamentally flawed beyond just reducing approval timeframes. It does not have the ability to be responsive, to support the enterprise in maximizing available technology and adapting to new operational concepts needed to win in the INDOPACIFIC fight. It needs to be reimagined.

“The technology is there. It’s our ability to understand it, have the people to employ it, and, most important, it’s about our ability to learn and take chances and do something different.” Jared Summers, former 18th Airborne Corps Chief Technology Officer

Recent comments from the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, ADM Grady, show that he appreciates the need for reform as well even if his approach deviates from some of the tenets we will propose.

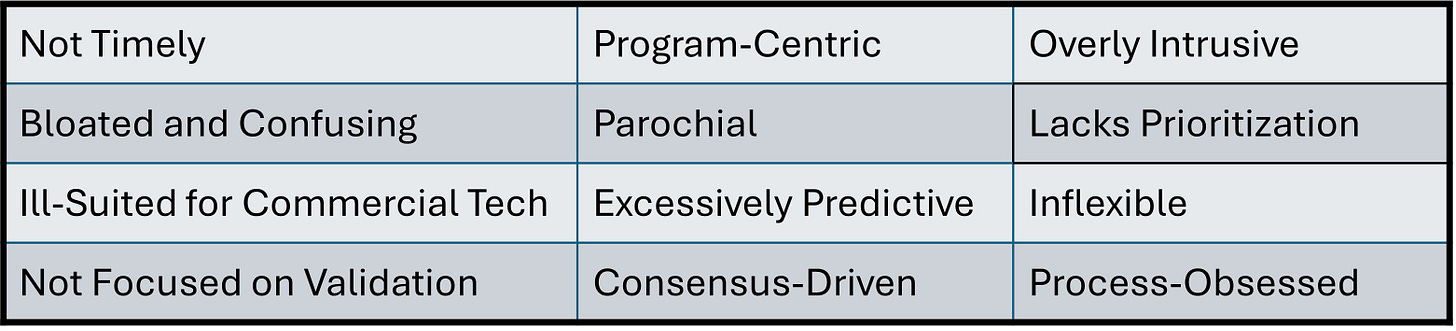

Current Challenges

There are numerous challenges with the current system that require illumination.

Not Timely. The process to conduct the multiple analyses, assessments and approvals adds little value but drives significant time lags. A recent GAO study found that Joint Staff officials do not track the total number of requirements documents that have been validated nor do they consistently measure the time it took to gain approval. Of the programs assessed, GAO found that none met the JCIDS established timelines, and some exceeded 1,000 days for validation. This at a time when many leaders are asking for permission to move faster. There are other indications that the JCIDS process has resulted in extended acquisition timelines over the years. We need a system that is aligned with user needs but devoid of excess study/review paralysis.

Program-Centric. The system is structured to only view capabilities through the lens of a formal acquisition program. A requirements document does not account for the numerous elements across multiple programs that are necessary to complete a kill chain. This is one reason for Combatant Command (CCMD) discontent with the Services since individual programs rarely provide an integrated and joint capability. The prime example of this challenge is the Joint All Domain Command and Control effort which should provide resilient communication and networking paths for joint operations but that is disparately spread over multiple Service efforts. We need a system that doesn’t need to scrutinize and approve individual requirements but is focused on ensuring the larger picture comes together.

Overly Intrusive. The current JCIDS process does not distinguish between a smaller effort (say ACAT III equivalent) if the J8 Gatekeeper determines it meets ambiguous “joint” criteria or a “special interest” JROCM. This means that an ACAT III program could be getting the attention of the military’s highest ranking four stars. This is why many programs try to find ways to avoid being subject to the JCIDS gauntlet (or even some of the more onerous processes at the Service level). This is not the best use of the leadership nor the program office’s time - and does not result in capability being fielded on an accelerated timeline. We need a system that can focus on the attributes being provided by an array of systems (large and small) and assess if that is going to be adequate for the current and near-term threats and needs.

Bloated and Confusing. The JCIDS policy and manual are over 500 pages. The table of contents is 18-pages. It has a complex web of appendices, annexes, and enclosures. Service requirement shops and program offices struggle to navigate the different sections that could be hundreds of pages apart. While very prescriptive, it also requires each organization to create a document, absent a template, in hope of achieving compliance with the many reviewers. Despite the length, there are also numerous different “certifications” that must be obtained through the JCIDS process that are poorly documented in the policy and manual - but are only discovered through the coordination process. Many Service requirement processes are equally convoluted, partially because they reflect the structure of JCIDS. We need a system that is clear and transparent, achieving the intended goals with the minimum amount of process and bureaucracy.

Parochial. The military services are the primary generator of requirements which is ironic given the JCIDS system was established primarily to address issues with joint capability development. The Aldridge Study found the Services rejected alternatives if they were resident in another Service or outside their area of expertise. The lack of CCMD influence resulted in “capabilities being pushed to them rather than identifying and pulling needed capabilities.” Given its other shortcomings, the current system makes delivering joint capabilities and translating new joint concepts into warfighting capability much more challenging. It also ignores the fact that the Services are “increasingly interdependent at the operational level” despite the proliferation of joint interoperability standards that continue to miss the mark. We need a system that focuses on joint integration of capabilities and can nudge the Services in the right direction when they begin to develop stove piped solutions.

Lacks Prioritization. While there are many documented (and unfunded) requirements across DoD, there is no enterprise approach for reviewing and prioritizing them. As the GAO noted, “The JCIDS process has not yet been effective in identifying and prioritizing warfighting needs from a joint, departmentwide perspective.” This may be why it is so challenging for CCMDs to gain support for their immediate needs. The Services can deeply prioritize within their own valued domains and craft budgets around those needs. However, the ability to prioritize across domains to identify and address investment shortfalls in key areas is highly challenged in the current system. With potential defense budget cuts on the horizon, the ability to maximize available investment funds is critical. We need a system that, using clear analysis, can convey that a particular capability within a particular domain needs to be prioritized to the detriment of other important but less critical capabilities (say procuring unmanned underwater vehicles in lieu of combat vehicles).

Ill-Suited for Commercial Technology. Current processes are not configured to pursue lower cost, commercial solutions. There are strong biases towards pursuing unique over-engineered military solutions. A DoD report found that the analysis of alternatives (AoA) process often presupposes the type of material solution and constrains the scope of the assessment which results in less consideration of available commercial solutions. There is fear that continuation of this system will drive industry to abandon the defense market. This is especially important to avoid given the commercial sector is outpacing DoD in maturing emerging technologies. We need a system that is less focused on the specific solution or technology but on the outcomes generated. The different acquisition offices bear the responsibility of conducting continuous market research and tech scouting to ensure the most mature advanced technologies are fielded.

“The last thing in the world we want to do is tell them [industry] what to build. We want to go to them with questions, and we want to find out what they can do. What is the art of the possible, and what is it that they could provide?” Air Force Lt. Gen. Richard Moore, Jr. on Combat Collaborative Aircraft

Excessively Predictive. Current processes assume a greater ability to predict the future (operational needs, adversary threats, technology advancement) than is reasonable. For instance, the Joint Operational Environment 2035 document was written in 2016. Most capabilities require modernization almost immediately after being fielded to address new threats. The current process often characterizes solutions too early in the process and unrealistically expects the threat posture to remain consistent. This is reinforced by acquisition processes that baseline costs and schedules before development has been initiated which combined with the slow pace of delivery results all too commonly in acquisition disappointment. We need a system where requirements don’t need to be constantly updated because the goals are well understood, and the program office pursues mature technology that can be fielded quickly to maximize progress towards those goals using iterative strategies.

“In a world characterized by unpredictability and increasingly frequent surprise, there are heavy penalties for ponderous decision making and slow execution.” Richard Danzig in his Ten Propositions About Prediction and National Security

Inflexible. As VCJCS, Admiral Grady, noted the JCIDS process has a “tendency to Christmas tree things too much” and the reason for it was “that the requirements process is not adapted to iterative updates so operational sponsors feel incentivized to capture all potential needs for the foreseeable future.” The acquisition system also rewards program managers who avoid disruption of active efforts. Excessive coordination and senior approval levels for updates inherently reduce its adaptiveness. We need a system that embraces the chaos of emerging technology development since that is what will allow the U.S. to maintain its advantage.

"The character of war changes frequently. It changes every time you have a new weapon…today we are undergoing the most significant and most fundamental change in the character of war. And it's really, this time, being driven by technology." Gen Mark Milley at Eurasia Group Foundation

Not Focused on Validation. While the overall premise of the JCIDS process is to validate a requirement, most often the process is used as a means for OSD orgs to gather information on a prospective program, ensure there are hooks for it to comply with various standards and different functional procedures, and to ensure there is adequate funding. While a Capability Based Assessment (CBA) usually needs to be referenced, it can often be an outdated one. New CBAs require a lot of effort to complete and are of questionable value, especially if the right experts are not on the team. We need a system that dynamically conveys what is needed for the joint force and does not require individual validation that extends the time for a program to get underway.

Consensus-Driven. In the current approach, a draft requirements document is staffed across numerous offices all of whom have the ability to non-concur for almost any reason. This non-concurrence can be issued for any number of reasons. It rarely means that the requirement is not valid or that it should be more rigorous but often because the document didn’t contain information they wanted to see or did not mandate something important to their office. This approach of using a requirements document to hold a program hostage until they provide certain information unrelated to a validated need creates major delays and drives considerable rework on program offices and requirement shops. We need a system that focuses on ensuring the specific operational requirements are valid without a dozen other considerations that can be addressed separately in program execution slowing down the entire effort.

Process-Obsessed. The steps that it takes to get a requirements document through the wickets are often hyper-focused on following the established process. Questions regarding whether the right document type was chosen, the right level of information included, compliance with the format or any number of administrative or minutiae can and often do distract from the discussion around whether the requirement is valid, might be overly restrictive (given commercial tech advances) or might be met by another system in work. We need a system that is modern and is not constrained to bureaucrat preferences and administrivia.

The bottom line is that the current requirement processes do not provide the value commensurate with the time and energy required to execute them.

Positive Moves

While requirements reform is still stalled, there are some positive, albeit minor advances that can be built on.

Good Move #1: While the JCIDS Manual is still many hundreds of pages, it does now include a Software Initial Capabilities Document (SW-ICD) that has a streamlined content and approval process. Army headquarters noted that this allowed them to successfully “operate outside of the traditional requirements process” by which they mean managing requirements at a more reasonable level as befits modern software development. There is a continued worry that this expedited process is slowly being subsumed into the normal JCIDS quagmire as reports on its use are not compliant with the timelines mandated in the JCIDS Manual.

Good Move #2: Joint Staff is trying to assess capabilities across a broader spectrum using portfolio reviews that employ mission engineering practices and address opportunities, challenges, risk, and trade-space that enable the DoD’s strategic objectives. The problem is that they are pursuing this through a top-down approach and do not have adequate staff to undertake this significant effort. They are also disconnected with the CCMDs and Services as it relates to specific mission threads or operational plans. There seems to be a good deal of hubris in the Joint Staff shops though that they have the answer and only they can direct a viable way-ahead. This often ignores the significant industry market research occurring in the program offices and laboratories that often understand the technology space better than Joint Staff.

Good Move #3: DoD is progressing the Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC) starting with a breakdown of concept-required capabilities and working towards development of new doctrine. The JWC provides a vision or “starting point” for advancing joint fires, contested logistics, joint command and control and information advantage mission areas. It is still unclear how the JWC outputs are being used in the JCIDS process despite the rhetoric.

Good Move #4: CCMDs are being provided more means to solve their own needs through efforts such as the European and Pacific Deterrence Funds, through gaining some acquisition authority (Section 843 of FY24 NDAA), by hiring in-house technology officers and by standing up unique task forces. While this is a good move, it should be recognized as completely unnecessary if CCMDs had the key capabilities they needed.

Good Move #5: Defense leaders are planning to stand up a Joint Futures Command to address the future of warfare amid rapid technological change. There is recognition in some Joint Staff publications that a “campaign of learning” is needed to drive new operational concepts. The messaging on the future of this organization and how it will be used to drive new thinking has been notably absent in recent months and does not appear on the Joint Staff website. It’s possible to imagine that Gen Milley saw value in that organization, but the current leadership has put that on the backburner.

Good Move #6: The Undersecretary for Acquisition and Sustainment (A&S) stood up a Deputy Assistant Secretary for Acquisition Integration and Interoperability (AI2) office. It manages the Competitive Advantage Pathfinders (CAP) and conducts Integrated Acquisition Portfolio Reviews (IAPRs)…and serves as the primary A&S office for JADC2 efforts. In the FY25 defense budget, AI2 received a dedicated funding line for $12.8M. This is a promising step, but A&S is still a relatively minor stakeholder in the larger budget battles, so its influence is still TBD in terms of driving the new system we are proposing.

While these good moves are positive in many aspects, they also only represent a small fraction of the change that is needed to ensure the U.S. has a process for building a robust joint force that can be presented to Combatant Commanders when the balloon goes up. These positive steps need to be coalesced into coherent joint approach for understanding operational needs, assessing available options, conducting key tradeoff analyses and rapidly moving acquisitions forward while also having the ability to pivot when needed.

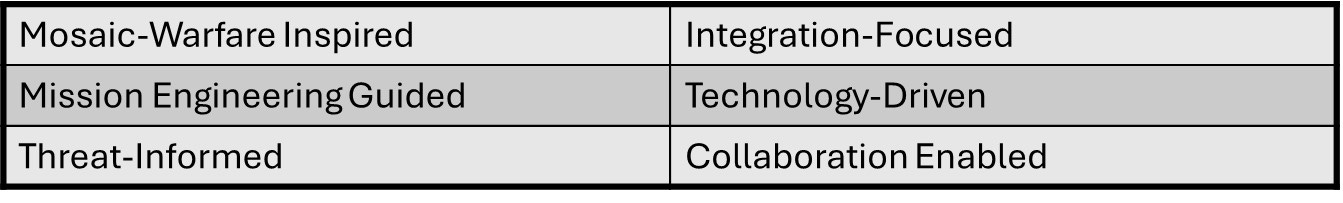

New Joint Requirement System (JRS) Tenets

This new imagined process cannot be executed only at the OSD-level, nor can the Services do it alone. There must be an appreciation for both top-down direction and bottom-up innovation. The struggle between near-term “fight tonight” needs and long-term “threat of tomorrow” requirements must be acknowledged. There must be a recognition that the opportunity space is enormous and only reasoned debate combined with continuous learning will unveil the best solutions.

The new Joint Requirements System should be based on the following tenets:

Mosaic-Warfare Inspired

Mosaic warfare was conceived at DARPA as a way of envisioning war in the 21st century whereby less monolithic weapon systems are relied upon in lieu of a system of systems construct whereby “any system having certain functional characteristics could be combined with others to provide a desired warfighting capability at the time and place of a commander’s choosing.”

With a focus on smaller, iterative and scalable capabilities, this approach needs to drive future DoD requirements and investment decision-making.

Integration-Focused

DoD needs processes and organizations to address cross-cutting functions and support integration of disparate capabilities into cohesive joint solutions.

Robust integration functions are critical to implement a mosaic warfare inspired vision and is the only way that (program-centric) capabilities deployed today can be assured to provide the effects desired within larger kill chains.

Mission Engineering Guided

A system of systems approach increases the level of complexity that must be managed as different systems with more discrete functions evolve over time.

The advent of mission and digital engineering tools and processes provides the answer for dealing with this complexity as mission threads can be mapped to existing or planned capabilities and digital models can more easily articulate the broader impact of smaller changes and better inform investment decisions.

This also provides a template for driving the joint force towards an interoperable and resilient architecture that can support a multitude of kill chains in a Service-agnostic environment.

Technology-Driven

Technology is advancing at a steady pace in some areas and at blistering speed in other areas. Michael O’Hanlon has identified key deployable technologies that he sees as advancing military capabilities in the now to 2040 timeframe.

Revolutionary: Computer hardware and software, offensive cyber operations, system of systems, AI, robotics and autonomous systems.

High: Chemical and bio sensors, laser communications, quantum computing, explosives, battery-powered engines, rockets, armor, stealth, satellites, rail guns and lasers.

There are more defense tech startups focused on defense than ever before and they are coming in growing waves (McKinsey study).

The Army War College analyzed several emerging technologies such as AI, biotech, quantum, nanotech, autonomy and robotics and found that many of these new technologies would likely converge in unique and interesting ways for the military and its future needs.

Threat-Informed

Adversary threats, especially from China, grow everyday as foreign leaders hostile to the U.S. or the western order strive to find ways to advance their position and gain control over elements of power.

The need to keep abreast of threats is apparent in DoD’s annual updates on China’s military and security developments to appreciate how challenging the next great-power conflict is going to be for the U.S. military.

Collaboration-Enabled

The future requirements system has to be enabled by collaboration. Effectively prioritizing needs and conducting tradeoffs requires the cooperation of many senior stakeholders both within government and industry.

Some leaders are pushing for a stick or mandate to force certain decisions, but the more powerful and enduring approach is to coerce through persuasion using the available facts and supported by accurate modeling.

“Sustained collaboration and shared technical expertise across the Joint Staff and CCMDs are necessary to confront the complex technological problems of today and the future.” Lt. Gen. O’Brien

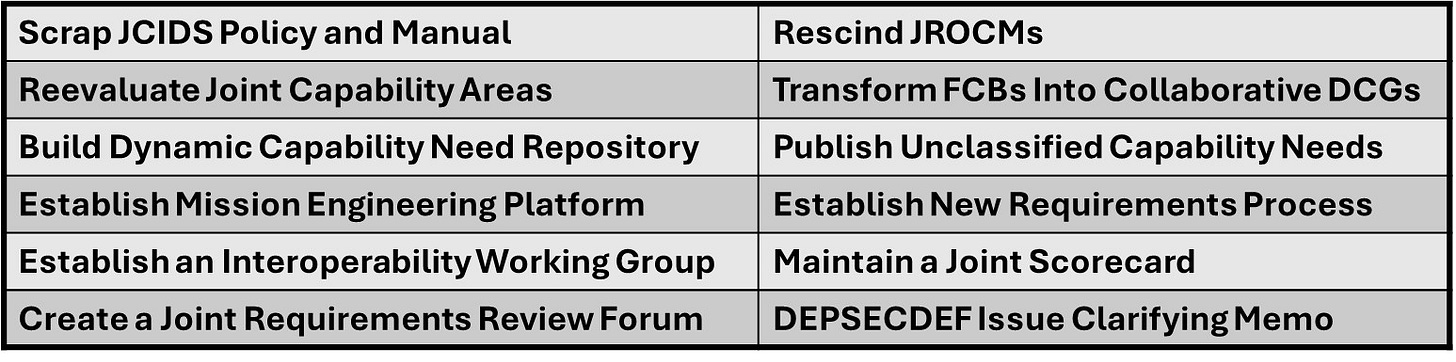

WAY AHEAD

(Joint Staff) Immediately scrap the current JCIDS Manual. It has been iterated on twice in recent years and has only gotten longer, more entrenched in legacy processes, and more incongruent with congressional direction.

(Joint Staff) Rescind JROCMS that require a program to obtain JROC approval.

(Joint Staff & Service Requirement Orgs) Initiate a reevaluation of the Joint Capability Areas to identify a more optimal structure that is more commonly understood by the broader workforce and logically connects to other constructs, such as JWC.

Consider replacing JCAs with the JWC lines of effort: Joint Fires, Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2), Contested Logistics and Information Advantage.

Consider including new elements like “Space Control” that are emerging critical areas that need to be given dedicated attention given the maturation of operational concepts they are undergoing.

This update will better support portfolio planning at the OSD-level that can be more logically linked to the different PEO portfolios.

J-6 currently has an outsized role given it covers “command, control, communications, and computers/cyber” which in an increasingly software-enabled military covers almost every weapons system.

This could be broken down into more manageable segments related to networks, data pipelines, artificial intelligence and software.

Cyber could be given its own primary designation given its increasing importance and the key differences between defensive and offensive capabilities.

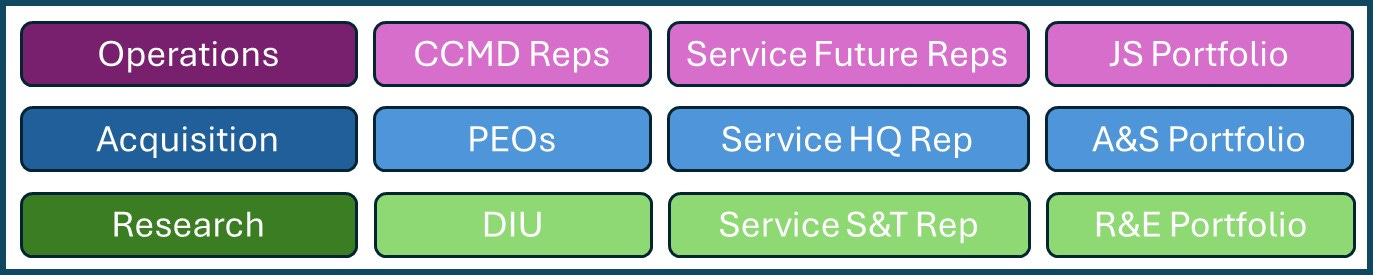

(Joint Staff & DCG Representatives) Transform current Functional Capability Boards (FCBs) into Defense Capability Groups (DCGs).

The FCB to DCG shift moves the function from a Joint-Staff led, decision-making body to a collaborative, multi-functional group.

The composition includes representatives from the OSD portfolio shops, CCMDs and PEOs.

The membership is intentionally small to avoid it becoming unwieldy.

The number of DCGs will correlate to the number of new capability areas established.

The DCG will not replicate but will pull expertise / findings from the various Services Core Functional Teams. Current Joint Staff CFTs can be shifted into a new DCG.

These groups will conduct the mission engineering analysis for their capability area to assess if the current capability gaps are comprehensive and if the efforts underway / fielded to satisfy those gaps are adequately covered.

These groups will support the execution of the Joint Staff Capability Portfolio Management Reviews (CPMRs) and will incorporate findings from:

Integrated Acquisition Portfolio Reviews (IAPRs) that A&S conducts.

Technology Modernization Transition Review (TMTRs) that R&E conducts.

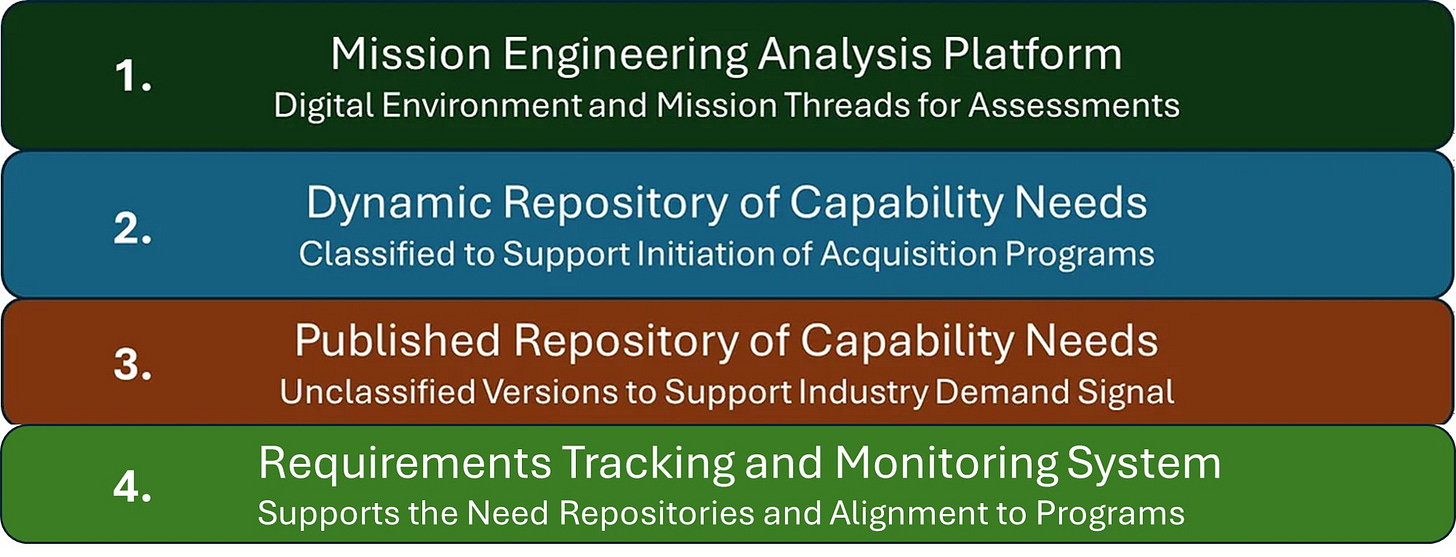

(Joint Staff & Service Requirement Orgs) Implement 4 main lines of effort to support more dynamic requirements management:

Establish a Mission Engineering (ME) Analysis Platform

While ME models and analysis will continue to be conducted by different organizations across DoD, Joint Staff should work to establish a common environment “ME Sandbox” that provides access to relevant data sources at different classification levels and appropriate software tools.

Access to this environment will be provided to the CCMDs, various OSD offices and the Service requirement / acquisition organizations - and contributed to by those same organizations (two-way transfer).

To support analysis in this environment, a Joint Staff office will maintain sets of mission threads that correspond to active OPLANs, CCMD contingency plans, and new operational concepts.

R&E currently has much of this responsibility but is ill-equipped and culturally misaligned to manage this for the enterprise. Some R&E experts should be requested to join the Joint Staff office.

Analytic results will be stored in a repository for other organizations to access to permit reuse and also provide transparency.

As articulated by Dave Tremper (DASD, Acquisition Interoperability and Integration), this will enable analysis to answer questions such as:

What are the key mission performance measures?

What are the capability gaps with respect to specific missions, and how will new capabilities change the way we fight?

How do new capabilities best integrate with or replace current systems?

And how can we optimize that balance in an integrated and affordable way?

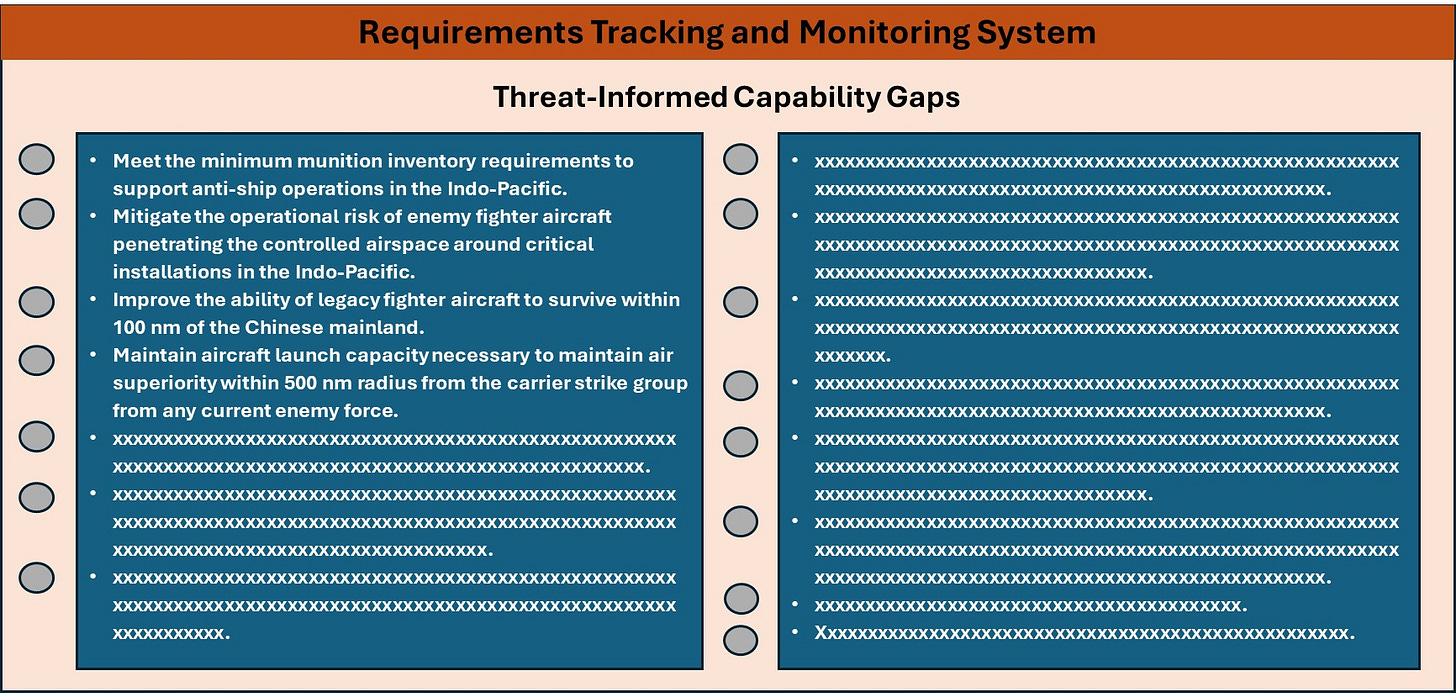

Create a Dynamic Repository of Capability Needs

Joint Staff J-8 will compile a comprehensive list of all capabilities that are required to effectively meet the NDS and achieve the required Joint Force.

This will be based on documented concept-required capabilities), threat assessments, CAPE studies, Capability Gap Assessments, JWC outputs, and inputs from the Combatant Commands and the Services.

These will be compiled into the Joint Requirements Tracking and Monitoring System or JRTMS.

These requirements will be classified at the respective levels with instances on SIPR and JWICS.

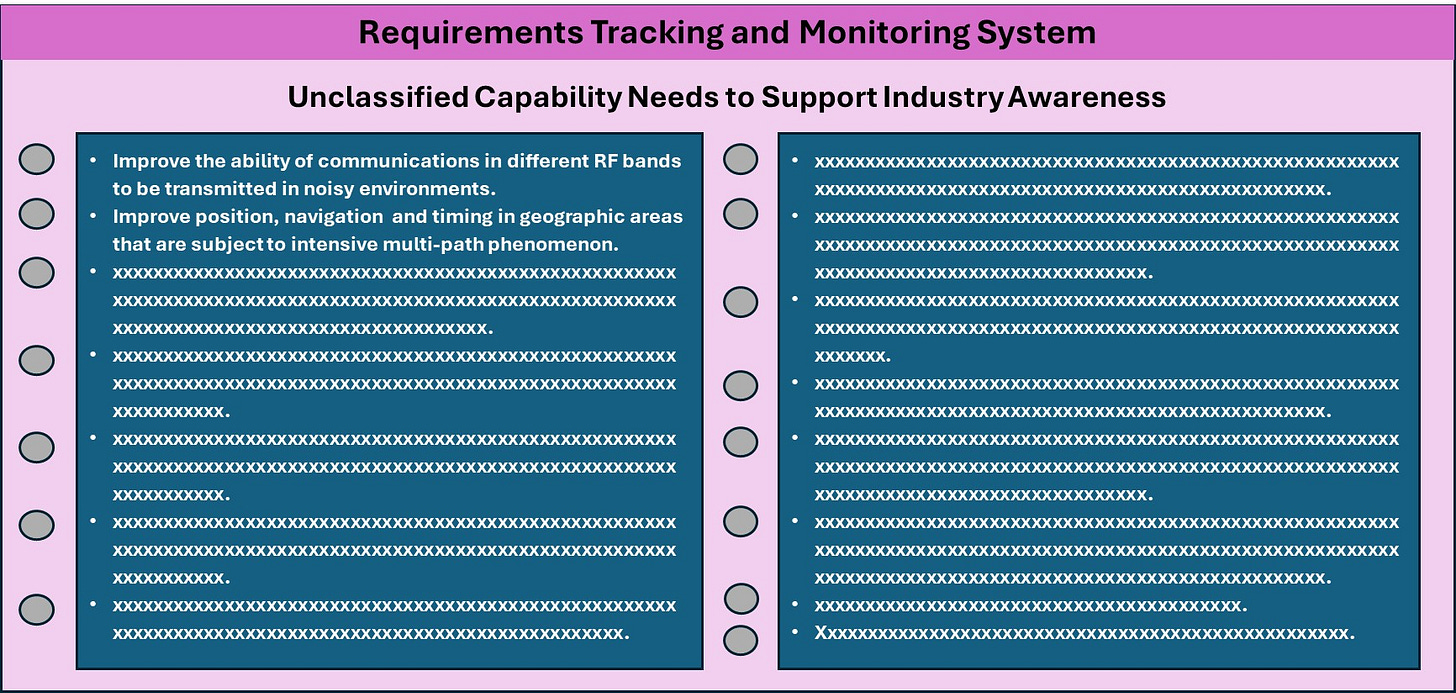

Publish Repository of Unclassified Capability Needs

Using the repository of capability needs as the baseline, a list will be curated of unclassified capability needs to be published and disseminated to various channels for industry consumption.

This should be published and updated on a quarterly basis.

The DCGs will compile the proposed list for their portfolios but Joint Staff will have responsibility for curating the final capability gaps, with A&S and R&E having responsibility for dissemination to industry.

Can be incorporated into R&E’s Innovation Pathways site.

Can be leveraged to support A&S’s industry concierge effort.

Given the issue that many potential industry partners have accessing the various solicitations across DoD, this published list can consolidate some of the SBIR Open Topics, Commercial Solutions Openings and other solicitations on SAM.

To avoid classification issues, these gaps can be written as Challenge Statements.

This will serve as a demand signal to industry on what areas they need to focus on to ensure their products have a chance of being selected and funded to meet a DoD priority need.

The lists will be maintained in the JRTMS system for access by any DoD office.

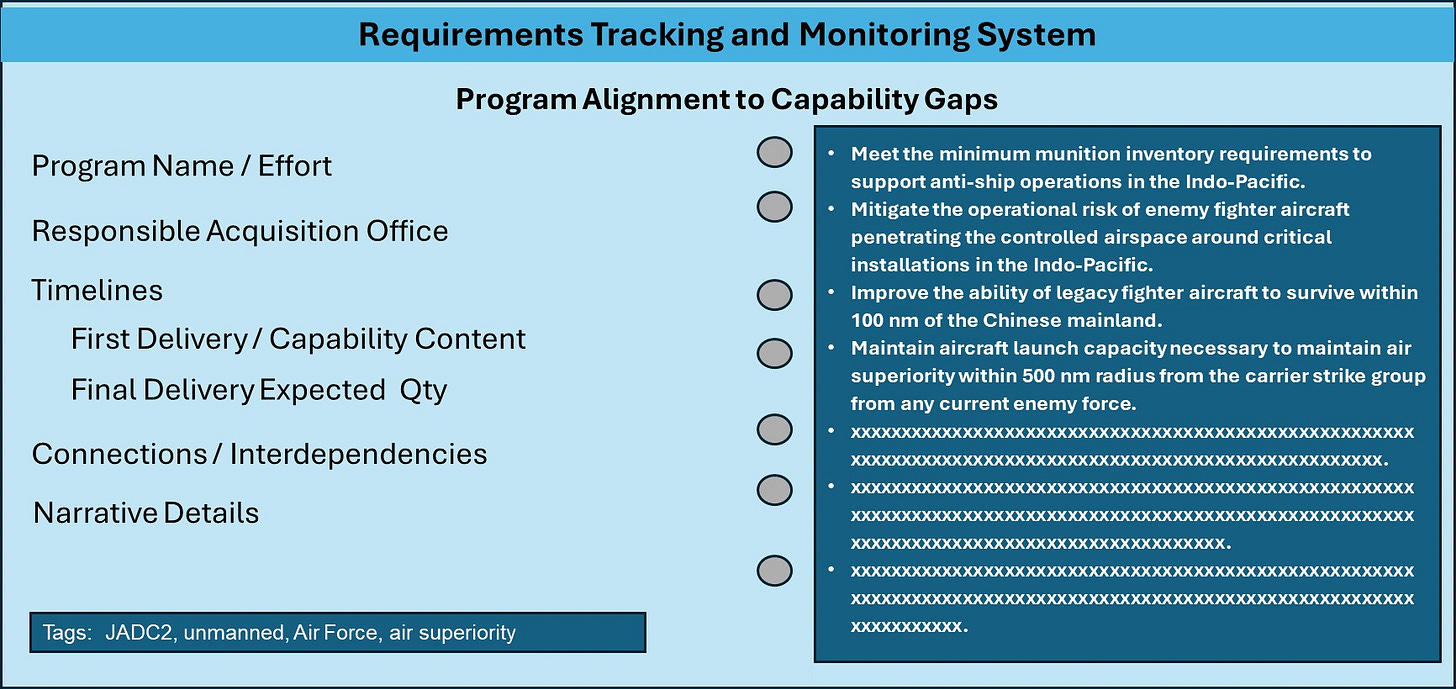

Create a Requirements Tracking and Monitoring System

The DCGs would need to provide suggestions to a Joint Staff team to map out the specific functionality and data fields needed and should leverage existing work that may have already been accomplished.

Will provide all the functions needed to document and track capability gaps at different classification levels.

Will maintain repositories for easy access by different DoD stakeholders.

Will support the new requirements management process.

Will pull select data from existing systems such as DAVE, PMRT, RDAIS and ADVANA.

Will be accessible to a broader swath of the acquisition workforce than KMDS is currently.

(Joint Staff & DCG Representatives) Formalize New Joint Requirements Process

In lieu of prescriptive ICDs and CDDs, the Services will simply input their programs, select the capability gaps that are being addressed and provide a few other key details that would be important for follow-on analytics.

CCMDs, DIU and other OSD offices can input their prototyping or fielding efforts underway.

Updates should be made quarterly to the system with more details available as they get closer to fielding. Ideally, programs would provide their digital models that can be ingested and used to support mission engineering analysis.

Standardized sets of metadata tags that can be applied to each program to allow for easy sorting. These could include any number of fields that might be relevant to the different users of the system.

This approach ensures that the wide coverage of investments can be understood and characterized as it relates to satisfying specific capabilities.

This will allow the DCGs to have a better sense if the efforts between the Services and other organizations are adequately addressing the capability gaps that were identified.

If there is adequate coverage, then a high confidence level can be provided to the Chairman and the DCG can act in more of a monitoring role.

If there are still numerous gaps, the DCG will compile recommendations for the Joint Requirements Review Forum to adjudicate and potentially result in formal recommendations to the Service Chiefs and Secretaries.

These gaps can be documented in the semi-annual scorecard and elevated to DEPSECDEF / SECDEF attention for discussion / action - and potentially resource decisions during the next budget cycle.

This approach provides visibility across the Services into the various efforts that are underway - opening the potential for more partnerships and co-development. Today, this type of sharing is personality-driven.

This approach also allows the Services (PEOs) to execute requirement tradeoffs at their level with the programs postured to provide the latest cutting-edge technology but being bounded by cost and time constraints.

Instead of conducting these laborious tradeoff discussions using static documents, they are conducted through negotiation and use of prototyping and experimentation as the program progresses in conjunction with users.

The Space Development Agency model can be adopted by the Service requirement organizations where they meet with their warfighter council every 6 months and have bi-weekly meetings in-between.

The new Joint Requirements System must rely on this type of dynamic communication and decision-making to stay abreast of the latest advances.

It also allows for exercise and experimentation feedback to be incorporated into the continuous tradeoff discussions.

Other information needs from the various OSD offices (such as intel support or cybersecurity planning) can be provided by the program through other means.

(Joint Staff & Service Requirement Orgs) Establish an Interoperability Working Group to address data and network interoperability using modern approaches.

Abandon the Net-Centric mandates that have been required for years and achieved little in way of multi-domain interoperability.

Adopt the 5G reference model approach to solving interoperability challenges.

Focused on delivering working implementations of an interface or concept.

Driven by two-sided incentives that maximally leverage government funding and industry knowledge.

This approach will better support meeting the goals of the JADC2 Strategy:

Meta tagging criteria

Data Interfaces

Data Availability and Access

Data Security

(Joint Staff & Services) Establish a new non-voting group (Joint Requirements Review Forum) comprised of the 3 stars with requirements responsibility roles at the Service level, the Director of Joint Staff, J-8, Acquisition Military Deputies, the DIU Director and the Combatant Command J-8 Directors.

This replaces the Joint Capabilities Board (JCB) functions and shifts from a decision-making body to a coordinating and advisory forum.

The 3-star level is more manageable to have detailed discussions but where the level of insight is commensurate.

The JROC stays in place but only meets for highly select decisions and primarily to review recommendations going to the DMAG.

The Vice Chiefs instead focus on refining the JWC and finalizing supporting doctrine, while executing their other significant duties.

This forum will focus on synchronizing modernization efforts across the Services and creating partnerships to ensure joint integration.

The inputs for this forum will come from the Defense Capability Groups and be driven by capability gap analysis and mission engineering analysis.

The outputs of this forum will be recommendations to the Service Chiefs and Secretaries (as well as the DMAG) to identify where adjustments may be needed. These could be:

Financial concerns such as underinvestment in a critical area.

Capability gaps not being addressed in a relevant timeframe.

Excessive overlap in efforts that risk impairing joint integration.

Acquisition acceleration of certain available technologies.

(Joint Staff) Maintain an internal “Joint Scorecard” for the Services that is briefed semi-annually to the SECDEF and DEPSECDEF.

Recognizing the Services need to be held accountable to support the Joint Force, the Chairman can use this tool to convey status and identify areas that need to be addressed in the new Joint Requirements System.

Examples of how the scorecard might be structured:

The DCGs provide a “confidence level” that their respective capability areas are adequately covered with the different investments underway or conversely, they identify areas of weakness.

Near-term operational challenges can be road mapped (like Defense of Guam) and progress tracked at each update.

Capability areas can be identified where the Services need to maintain a certain level of investment. A target percentage of TOA could be established:

5% investment budget to support offensive and defensive cyber.

10% investment to support munitions procurement and upgrades.

10% for unmanned hedge investments to offset traditional force.

Areas of resistance could be noted where the Services are not sharing information or not actively coordinating in key areas that are needed to integrate joint capabilities.

The Deputy’s Management Action Group can be used to track DEPSECDEF /SECDEF direction and ensure implementation before next reporting period.

(Deputy Secretary of Defense) Issue a memo:

Rescinding DoD Directive 7045.20, "Capability Portfolio Management” and many of the noted meetings and detailed responsibilities.

While the CPMRs, IAPRs and TMTRs should continue as they involve valuable collection of data and good discussion, the DCGs should act as the primary venue to hold these detailed discussions and propose a way forward.

There are other excessive meetings and products in this directive that will only serve to burden the acquisition community with reporting. That should be minimized in preference to products produced by the DCGs.

Direct the Service Secretaries to be cooperative partners in this effort with a bias for transparency by ensuring that:

Service Acquistion Executives and Program Executive Officers populate the JRTMS with program and investment data to kickstart this new approach.

Requirement shops adjust their current processes to align with this new more adaptive approach.

Convey the vision that excessive duplication of effort and unsynchronized activities will not benefit military service members when they are deployed into conflict under a Combatant Commander who must conduct systems integration activities while executing their primary role of defeating enemy combatants.

Conclusion

The requirements system does not need to involve reams of stale documents and tables full of performance specifications to adequately inform the start of an acquisition program. With the increased use of prototyping, experimentation and multi-phase down-selects, there are many opportunities for the users to influence the direction of the program based on the current state of technology and other goals. A requirements document is not the “last word” as it usually viewed today.

The energy spent on these low-value discussions distracts from the more important task of comparing (and updating) capability gaps to solutions that are under development and ensuring that there is adequate coverage of those needs to support the warfighter in operationally relevant environments. The new Joint Requirements Systems shifts the focus from a top-down directive approach to requirements and instead posits a more collaborative but accountable system where more dynamic decisions can occur using more modern constructs.

Defense Tech and Acquisition is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.