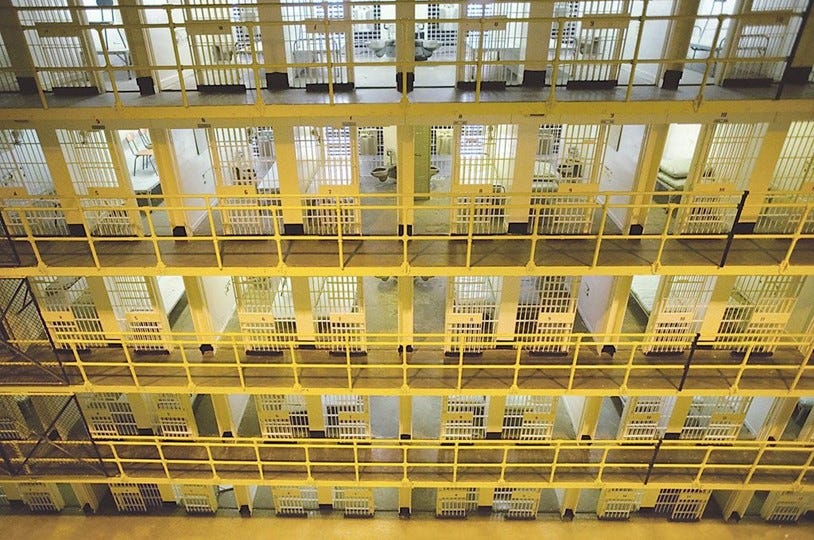

DoD’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) system locks up the annual defense budget into many appropriations and budget activities that provide an accounting-level breakdown into discrete activities. This is extremely helpful for auditors and budget overseers but severely complicates DoD’s ability to move funds to efforts that are ready to be scaled or integrated to provide an operational capability.

In DoD parlance, appropriation categories are often referred to as “colors of money.” These include:

Research Development Test and Evaluation (RDT&E)

Procurement

Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

Military Personnel (MILPERS)

Military Construction (MILCON)

Within each appropriation, there are different subcategories called “budget activities.” Each budget activity (BA) is unique to the appropriation in which it resides.

Within Procurement, there are 40 different BAs that cover items such as ships, aircraft, missiles, ammunition, combat vehicles, and support equipment.

Within RDT&E, there are 8 BAs, also known as 6.1-6.8 accounts. These span the research and development lifecycle, with the exception of BA-8 which is a pilot program for software acquisition (limited to a small number of programs).

Basic Research

Applied Research

Advanced Technology Demonstration

Advanced Component Development and Prototypes

System Development and Demonstration

RDT&E Management Support

Operational Systems Development

Software and Digital Technology Pilot

The chart below outlines the breakout of RDT&E 6.1-6.8 accounts over the last 26 years. We generally think of the 6.1-6.4 accounts as Science and Technology and 6.5 as formal development (think major programs). The 6.7 account is generally larger given it is intended to upgrade fielded systems (of which DoD has a lot) and it also includes classified pass-through funds.

While these BAs are intended as accounting measures to track where funds are being used, they also constrain defense budgets into walled off segments. As technologies and programs progress through their lifecycle, if they weren’t precisely planned, programmed, and budgeted two to three years out, then disconnects can arise that leave programs stranded without the ability to continue tech maturation while also not able to progress to the next phase.

There may also be changes to military needs that drive a requirement for more of one item (say tanks) and less of another (say support equipment). The current rules would not allow those funds to be moved to buy more tanks.

If a program no longer requires the funds (say it was terminated), they can also not able to be easily moved to a higher value activity.

When it comes to scaling commercial technology (something we have been major proponents for), these BAs may not allow acceleration to production. If you’ve read about the recent Replicator effort announced by the Deputy Secretary of Defense, then you can appreciate the challenges of moving funds to support massive levels of unplanned procurement in the year of execution under these restrictions.

To move funds from one purpose to another requires DoD to seek a reprogramming action. These reprogramming actions require all defense committees in Congress to agree (not always easy) can and often do take multiple months which drives operational risks and delays to programs…and ultimately the warfighter.

What if DoD simplified investment budgets into three primary appropriations:

Research

These funds would be used for investments that are not tied to a specific acquisition capability but rather focused on exploring and maturing defense unique technologies. These funds would primarily be executed by academic institutions and laboratories. This would consolidate the first three RDT&E BAs that includes basic and applied research along with advanced technology demonstration. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) funds would also be executed out of this account to advance commercial solutions for defense needs.

Development

These funds would be used for investments that prototype, develop, integrate, test and upgrade a specific capability. The primary focus of this account would be to rapidly execute the activities necessary to enable a capability to be fielded to the warfighter. This would preclude the current “valley of death” challenge that programs encounter moving from prototyping to development. This appropriation consolidates the remaining five RDT&E budget activities.

Procurement

These funds would be used to produce systems and/or acquire them “off the shelf”.

Congress and DoD would still allocate funding to individual budget line items but would leave flexibility for funds to be internally reprogrammed if a production line on one program is operating slower than expected or the warfighter prioritizes the need for additional radars over buying extra support equipment. Combined with other reforms that increase reprogramming thresholds and allow some new starts in the year of execution, this would accelerate the ability to scale commercial solutions in a timely fashion…a challenge that has been sharply noted in the startup community. It would also help ensure that the warfighters receive the technology that will provide the greatest impact since conditions can change within the lengthy budgeting cycle.

Congressional Concerns

Control

To some extent this approach would limit the ability of congressional appropriators to precisely control and “lock-in” funds to a particular activity. However, in this era of Great Power Competition, compromise is needed that provides a reasonable balance of control that preserves constitutionally-granted rights of Congress and also ensures that DoD can meet its critical national security responsibilities. Mitigations can be put in place that require consultation with the defense committees for reprogramming funding above certain thresholds, yet they must be raised above the tight controls in place today. This requires rebuilding trust between the DoD and Congress to include active collaboration on strategies, priorities, and progress.

Insight

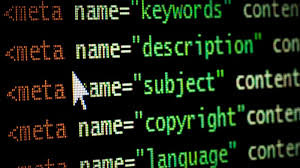

The loss of detailed budget activities is likely to cause heartburn with some appropriators. However, the fact that these constraints are not applied proactively does not preclude them from being applied retroactively. Detailed accounting can be maintained through the use of meta-tagging with categories negotiated with the defense congressional committees in advance. This would provide the same level of insight (perhaps even greater) while not artificially constraining flexibility that might be needed to deliver key military capabilities.

The PPBE Commission established by Congress has already highlighted some of the challenges in their initial report.

A single major acquisition program often has multiple budget lines and budget activities (BA), making it difficult for Congress to track the entire program, and even more difficult for the Department to manage the program. While these BLIs were all developed for a reason—they reflect congressional, Department, regulatory, historical requirements, and precedent—it is not always clear that the historic reasons for developing a separate BLI still apply today.

We hope their final report will propose some serious reforms to address these challenges. Time is of the essence and we cannot afford to wait for everyone to be totally comfortable with change because our adversaries are certainly not waiting.

This logical compromise can have a real impact on solving key issues with the tech transition “valley of death” and untimely delivery of capabilities to our warfighters.

Thanks for this thoughtful piece. It also applies to NASA. I would argue that drawing a boundary between research and development is also perhaps too far, as R&D is not a linear, but a cyclical process. Venky writes in the most thoughtful way I’ve seen yet in these two books: Cycles of Invention and Discovery https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674967960; and the Genesis of Technoscientific Revolutions https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674251854

Another great article! I totally agree again. My favorite passage was this one, because I think it's true for most of the oversight concerns and granularity tradeoffs in collapsing budget lines:

"However, the fact that these constraints are not applied proactively does not preclude them from being applied retroactively. Detailed accounting can be maintained through the use of meta-tagging with categories negotiated with the defense congressional committees in advance. This would provide the same level of insight (perhaps even greater) while not artificially constraining flexibility that might be needed to deliver key military capabilities."

There may even be ways to tag lines proactively but not prescriptively, suggesting what is the "probable plan" but still protecting flexibility. Here I am thinking of differentiating meta-tagging from budget structure, with the conceptual equivalent of technological maturity being simply an attribute of an activity rather than a guarantee of particular spending activity